Saturday, 25 April 2009 14:11 UK

For as long as South Africa’s opposition parties champion pro-business policies, they will fail to threaten the power of the incoming African National Congress government, led by the controversial Jacob Zuma. Most poor black South Africans see the long-established Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which retained its status as the official opposition in the national election, as the political front of white business, and the newly formed Congress of the People (Cope), which came third, as that of black business. With their combined vote being more than 20%, the two parties will now be under pressure to merge to effectively challenge the ANC in the 2014 election. “We’ve got to realign politics in South Africa and that’s what I’m going to spend the next five years doing,” said the DA leader, Helen Zille, after the election. As South Africans vote for parties, not constituency MPs, realignment is possible only if the DA and Cope merge. But this is unlikely to happen within five years, because of personality, policy and racial differences between the two parties. And the reality is no party can beat the ANC, which has existed for nearly a century, without striking a chord with South Africa’s shack-dwellers, farm workers, job-seekers and domestic workers. Pressure to deliver These are the people who gave Mr Zuma a decisive victory but they also pose the biggest threat to him and his party. They are part of the “social movements” that have emerged in South Africa since the end of apartheid in 1994 to campaign around bread-and-butter issues.

“Police statistics show there are about 8,000 protests a year in South Africa, mainly over service delivery issues like access to water, housing, land, education and health,” says Professor Patrick Bond of the Centre for Development Studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. “Per person, this is the highest number of protests in the world. They are part of the resistance culture [forged during the anti-apartheid struggle].” Some of the protests have been reminiscent of the struggle against white minority rule: burning barricades, running battles with the security forces and attacks on the home of ANC officials. The question is: will the Zuma-led government deliver on its promises or will the protests spiral out of control? “Zuma tapped into a dramatic change in the mood of South Africa’s poor black majority,” says the Johannesburg-based political commentator, William Gumede. “Forgotten by the elite, they have run out of patience and are now demanding the economic dividends of democratic rule. “He is unlikely to have the honeymoon period enjoyed by past ANC governments. If he fails to deliver, the poor will also turn against him.” And the list of issues on which the Zuma government has to deliver is long. Economic risk In its manifesto, the ANC promised a Canadian-styled National Health Insurance System; a “food for all” scheme; “adequate housing” for the military veterans who fought white minority rule; more child grants to poor families; bringing down “unacceptably high” levels of unemployment and “universal access” to water and sanitation by the time of the next election.

To fulfil these promises it is essential for the ANC to avoid the fate of other African liberation movements that swept to power on the back of support from the poor. Preferring anonymity, a former anti-apartheid activist who campaigned for an ANC victory says: “Once in power, liberation movements tend to run into really serious trouble after 20 or 30 years. The ANC has been in office now for 15 years, so it has to deliver – and deliver on a big scale.” Mr Bond says that inequality levels have worsened since the end of apartheid, with statistics showing that “South Africa is now the most unequal country in the world”. But he says the Zuma government will battle to meet its promises because “technically South Africa is moving into a recession” and has been cited in the Economist magazine as the most risky emerging market. One of the most pressing matters in the new president’s in-tray will be what to do about Trevor Manuel, who has served as finance minister for more than a decade. There has been intense speculation in both the South African and international media that he will be reappointed despite the fact that Mr Zuma’s main backers – the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) – accuse him of pursuing “neo-liberal” policies, and have been demanding his ousting. But the reports say Mr Manuel may only be appointed for a “transitional period”, a compromise that Cosatu and the SACP are likely to accept. However, Mr Bond of the University of KwaZulu-Natal warns Mr Zuma should give the issue careful thought. “Manuel’s wife, Maria Ramos [who was until recently the top civil servant in his department], is now the head of South Africa’s biggest bank,” he says. “So for her and Manuel – the country’s chief financial regulator – to be in the same house will be a major conflict of interest.” And Mr Zuma’s poor constituents could interpret it to mean that their president was continuing with the former government’s “crony capitalism”, which saw ANC-allied businessmen and politicians enriching themselves at their expense

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8018267.stm |

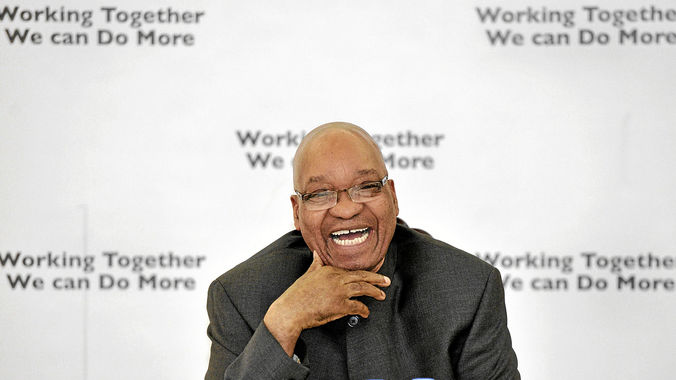

Analysis: Zuma’s challenges