By Lauren Tracey on June 22, 2015 — If young people are to be the foundation of a brighter future for South Africa, they need to be nurtured correctly and empowered with education and knowledge of the quality they deserve.

High school students in Soweto, June 16 1976. Image: Bongani Mnguni, City Press, Gallo Images, Getty Images

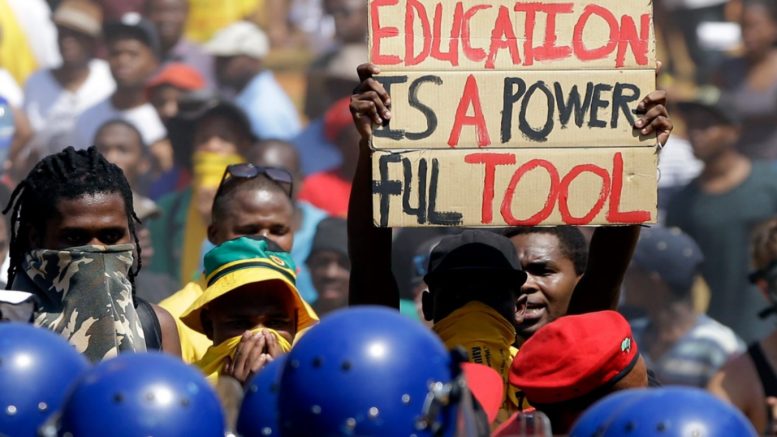

Last week, South Africa celebrated Youth Day, during which young people are commemorated, celebrated and acknowledged for rising up against apartheid and its unfair education system.

Every year, various government departments hold events across the country to remember the hundreds of young people who lost their lives in Soweto on the morning of 16 June 1976. But as we celebrate the sacrifices made by young people in fighting against apartheid, should we not also reflect on how far South Africa has come since the Soweto uprising 39 years ago? Has democracy brought the kind of progress in education that many people died and fought for during apartheid?

The Soweto uprising in 1976 took place as a series of protests against the use of Afrikaans and English as equal mediums of instruction in secondary schools. Students were not only protesting against the use of Afrikaans in secondary schools, however, but also against “the whole system of Bantu education, which was characterised by separate schools and universities, poor facilities, overcrowded classrooms and inadequately trained teachers.”

Four decades later, it should therefore be of great concern that a 2013 report published by the Centre for Development and Enterprise found that South Africa has, “the worst educational system of all middle-income countries that participated in a cross-national assessment of educational achievements.” The report goes on to state that the number of 18-24 year olds who are not in an educational institution, employed, or in training has increased from 30% in 1995 to 45% in 2011. Young people continue to be faced with overcrowded classrooms, inadequately trained teachers, textbook shortages and school infrastructure backlogs.

Last year, the Institute for Security Studies conducted a study aimed at understanding the factors that influence young South Africans’ voting behaviour. Poor education was identified as one of the top five most important problems facing the country amongst the 2 015 young people who participated in the research. Many participants said they felt that government has failed them where education is concerned. According to a 19-year-old male in Mpumalanga, “our government does not take our education seriously.”

In the Free State, a 23-year-old female woman said, “as black people, we struggle a lot. Especially when it comes to education, there are hardships that we have to go through every time when we [want to] have to access education. So I think if the government … can look at education and empower youngsters to get educated so that even our economy can improve … not to focus only on a certain portion of people, [but] on South African youth as a whole.”

An 18-year-old female from the Western Cape echoed these thoughts, saying, “I think the most important problem in South Africa today would be the schooling system. I have cousins who have gone to schools that do not really provide correct material for education … today they are not in school, they are not even in high school or university … [they] are in jobs that do not pay them enough to keep a family going.”

Although many young people express concerns about education, it is not due to a lack of resources being made available by government for education. According to the former minister of finance, Pravin Gordhan, there has been an increase in the number of schools that offer free education: from 40% in 2009 to 60% in 2014. This increased the number of children with access to education from five million to nearly nine million. Gordhan said that at least R254 billion (20%) of the country’s 2014/2015 national budget will be spent on education.

Of this, R40 billion (21%) goes to post-school education and training, while some R21 billion is set aside for university subsidies and R19 billion for the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS). In 2014 and 2015, however, the country experienced widespread protestsdue to shortfalls in financial aid.

That South Africa has made some progress in education cannot be ignored – particularly the fact that more young people are able to access primary and secondary schools, colleges and universities than was the case during apartheid. But while government has done a great deal in improving access to education, the quality of education also needs to be reviewed.

Many schools do not have access to resources and facilities such as textbooks, desks, libraries, laboratories and toilets. There is still much work to be done to improve the education system and during Youth Month, the focus should be on improving both access and quality of education to young people.

Students in Limpopo use umbrellas in their classroom because of a leaking ceiling. Image: Section 27

More than 50% of young people who start school will drop out before completion. Those who do stay are often unequipped to enter the job market or start businesses of their own due to sub-standard training in subjects such as mathematics. This contributes to our high levels of unemployment and poverty, and has deep-seated consequences for the future of the youth in South Africa.

If young people are to be the foundation of a brighter future for South Africa, they need to be nurtured correctly and empowered with education and knowledge of the quality they deserve.

This article was first published by the Institute for Security Studies, and is republished here with their permission.

Inadequate Education Continues to Undermine South Africa’s Youth