Compiled by

Ernst Roets and Lorraine Claassen

For the attention of the

International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims

A report by AfriForum

26 June 2014

International Day in Support of Victims of Torture

The Reality of

Farm Tortures

in South Africa

On this International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, we express

our solidarity with, and support for, the hundreds of thousands of victims

of torture and their family members throughout the world who

endure such suffering. We also note the obligation of States not only

to prevent torture but to provide all torture victims with effective and

prompt redress, compensation and appropriate social, psychological,

medical and other forms of rehabilitation. Both the General Assembly

and the Human Rights Council have now strongly urged States to

establish and support rehabilitation centres or facilities.

—United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon 20121

1 Secretary-General’s Message for 2012, International Day in Support of Victims of Torture

“

”

1. Introduction

2. Defining Torture

3. Day in Support of Victoms of Torture

4. Farm Tortures in the South African context

5. The Extent of Farm Attacks in South Africa

6. Characteristics of Farm Attacks

7. The Deprioritisation of Farm Attacks in South Africa

8. Lasting Effects of Torture

9. Case studies

1 Christine Otto

2 Edward and Ina de Villiers

3 Lena-Maria Jackson

4 Andre van der Merwe

5 Barbara Wortmann and Etcel Wortmann

6 Mohammad and Razia Enger

7 John and Bina Cross

8 Attie, Wilna and Wilmien Potgieter

9 Koos and Tina van Wyk

10 Fanus Badenhorst and Marina Maritz

10. Conclusion

Content

1. Introduction

AfriForum is a civil rights organisation operating in South Africa with particular

focus on the promotion and protection of the rights of minority communities.

The organisation was founded in 2006 and has been blessed with growth at an

exponential rate. At the time this report was drafted, the organisation had more

than 95 000 individual members, the majority of whom represent families.

AfriForum is a multi-issue, non-governmental organisation and therefore the

organisation drives multiple campaigns simultaneously. However, one of AfriForum’s

core campaigns is the prioritising of farm murders.

South Africa has been plagued by farm murders, especially in the past 20 years.

The worst of the matter is not the fact that South African farmers are being

attacked and killed, but rather the disproportionate numbers that are involved,

the extreme levels of brutality that often accompany these crimes, and the fact

that the South African government has largely been in denial about the problem

since 2007.

On 17 June 2014, during the annual State of the Nation Address, state president

Jacob Zuma said that the government expected the agricultural community to

create one million jobs by the year 2030. Although AfriForum agrees that poverty

and job creation are one of South Africa’s major challenges, the organisation

expresses concern that the state president’s ambitions will not be realised as

long as job creators in the agricultural community are being murdered and even

tortured at an alarming rate. Fifteen years ago, South Africa had about 100 000

commercial farmers. This number has declined to about 36 000 today.2 If the

crisis of farm murders and tortures is not addressed, it will impact negatively not

only on the agricultural community, but on South Africa as a whole.

About a month before the finalisation of this report, a new South African government

was elected. Together with this, a new minister of police was appointed.

Most of the information in this report is based on interaction with previous

2 Loss of commercial farmers ‘worrisome’ News24, 24 March 2013.

ministries of police (who were of the same political party as the new minister)

and national police commissioners.

Only days after the inauguration of Nkosinathi Nhleko as the new Minister of

Police, Martin Coetzee (82) was attacked and tortured on his farm near Belfast

in the province of Mpumalanga. Upon discovering and confronting intruders on

his farm, Coetzee was tied up and repeatedly beaten with blunt objects, breaking

his arm. From this particular case it transpired that there was a relationship

between the attackers and the local police, as the attackers called the police

to the scene. The police arrived shortly after the summons, only to engage in

discussion with the attackers while ignoring Coetzee, who was still on the scene,

tied up and severely injured.

This report will be presented to the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture

Victims (IRCT), but also to the new South African Minister of Police, Nkosinathi

Nhleko.

After several calls for the prioritisation of farm murders had fallen on deaf ears,

AfriForum decided in 2013 to internationalise its campaign as a way of raising

awareness about the matter and obtaining support. With this report, AfriForum

intends strengthening communication with the IRCT in order to learn from best

practices how the phenomenon of farm murders can best be addressed, while

supporting the victims who have been tortured, or who have lost loved ones

during these attacks.

The case studies in this report were compiled using various resources and articles

published in the media. All resources are available on request. As is stated

elsewhere, limited resources were available regarding the more sensitive details

of some of the attacks mentioned in this report.

The most widely accepted definition of torture internationally is set out by Article

1 of the United Nations Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT).

The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims further explains that

torture is often used to punish, to obtain information or a confession, to take

revenge on a person or persons or to create terror and fear within a population.

Some of the most common methods of physical torture across the globe include

beating, electric shocks, stretching, submersion, suffocation, burns, rape

and sexual assault.

‘… “torture” means any act by which severe pain or suffering,

whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted

on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a

third person information or a confession, punishing him for

an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected

of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a

third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of

any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at

the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a

public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

It does not include pain or suffering arising only from,

inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.’

2. Defining torture

3. Day in support of victims of torture

26 June is a day of particular importance when it comes to the issue of torture.

The day is dedicated to support of victims of torture on the United

Nations’ calendar. On the 26’th of June 1987, the United Nations Convention

Against Torture came into effect. Furthermore, the Charter of the United Nations,

which is the foundational treaty of the United Nations, was signed on

the 26’th of June 1945. The Charter states in article one that the United Nations

intends to take effective collective measures to the suppression of acts

of aggression (among other).

The General Assembly of the UN officially decided to dedicate the day to

support of victims of torture at the proposal of Denmark, which houses the

International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT). Since then,

nearly 100 organisations across the globe organise events, celebrations or

campaigns on the said day.

The purpose of this day is to speak out against violent crime, to raise awareness

about incidents of torture worldwide and to support victims of torture.

Victims are limited to those who have been tortured and who were fortunate

enough to survive, but also those whose loved ones were tortured and killed.

4. Farm tortures in the South African context

Although torture may occur during a variety of violent crimes, with different

purposes and in various circumstances, it is particularly evident during farm

attacks (the focus of this report). The true extent to which torture may occur in

these cases is difficult to determine, as information on this subject is limited for

a variety of reasons, including:

The victims succumbed to the injuries inflicted during the attack and

the exact details of the ordeal are not known and cannot be relayed in

witness testimonies

Because of the ongoing investigations, only limited details and facts

are often released to the press and the public

The extent of the violence used on victims is often just too horrendous

to be released

The families of the victims need to be respected and should be

spared any additional pain and sadness that facts about the attack

may cause

The South African Police Service (SAPS) does not release any information

on the topic and has refused to engage with civil society on

the topic in recent years

It is clear that attacks in which torture occurs are loaded with emotion and

intent. In numerous cases the attackers may have had ample opportunity to

target the homestead when the inhabitants were not at home or were elsewhere

on the property, thereby reducing their chances of being caught. The crime

changes from theft to robbery, and from robbery to torture. What makes an

assailant then choose to use extremely violent and unnecessary means to inflict

pain and torture if the sole motive was monetary gain?

During the attack, the attackers are in complete control of the situation and

have the power or authority over the victim’s lives. In stark contrast to the torturer,

the victim (or tortured) has absolutely no control due to being physically

restrained and frightened about the uncertainty of the situation and whether

they will come out of it alive. It is disturbing that a group of assailants chooses

as a collective to disregard the morality and moral fibre that are part of every

human being (another subject entirely) and to inflict such extreme, brutal and

cruel suffering on another human being. One cannot deny the complexities

of group dynamics and the authority of the leader of the group, leaving other

members afraid to confront him in such a loaded situation. However, this subject

will not be dealt with here.

Nevertheless, these extreme measures are used for the purpose of gaining information

regarding the whereabouts of the keys to the safe, the safe itself or

the location of other valuables. The contents or the value of the possible loot

is at this stage still unclear in the majority of cases, and torture may have been

unnecessarily inflicted for a meagre R40.3

It is apparent in some cases that monetary gain was not the motive for the

attack. Attackers may have tortured their victims in order to instil fear, not only

in the victims but also in the general farming community. Torturing to such

an extent may also have been used to send a message and to let the victims

know that they were and still are being watched, instilling extreme fear.

Michael Davis4 writes that torture can be undertaken or used for any of at least

six reasons (of which the UC Convention identifies four):

To obtain a confession – ‘judicial torture’

To obtain information – ‘interrogational torture’

To punish – ‘penal torture’, and

To intimidate or coerce the sufferer or others to act in certain ways

– ‘terroristic’ or ‘deterrent torture’

To destroy opponents without killing them – ‘disabling torture’ and

To please the torturer or others –‘recreational torture’.

Any of these reasons still seem unconceivable to the rational mind. Even

though the victims are physically helpless and restrained, the torture is as

much on an emotional as a mental level. Regardless of the possible motive for

gaining information from the victim, the victim is left to face severe pain and

possibly death.

3 40 South African rands are roughly the equivalent of 3,74 US dollars or 20,54 Danish krone.

4 Davis, M. 2005. The Moral Justifiability of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading

Treatment, International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 19(2): 161-178.

What does a victim think about when being tortured for hours on end? Obviously

the safety of their spouse or family, and inevitably the tortured person’s

own life. Weighing up possible scenarios, negotiating with the torturer, pleading

for the torture to end are but a few possibilities of what a victim may have to

face during hours of torture.

Davis5 also discusses the duration of such an event. The torture may not necessarily

end when the information is given and the victim’s life may be taken

regardless of their having provided the correct information. The natural limit of

torture or stopping point of the suffering is ultimately death, when the victim

is physically not ably to endure or withstand the suffering and dies as a direct

result of wounds inflicted.

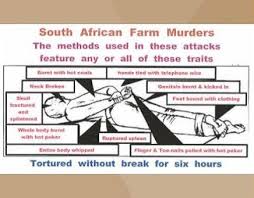

In the case studies included in this report, the variety of the methods of torture

is clear. One method that stands out and is often used is burning the victim

with a hot clothes iron. This not only shows malicious intent but the torturers

expect this method to provide them with the desired results. The use of an

iron or warming up of an object to use to burn a victim also indicates the time

the assailants have to complete an attack. They are comfortable in taking their

time, often helping themselves to food and drinks, trying on clothes and looking

for valuables throughout the house while torturing the restrained victim in the

meantime. There is no fear of being caught on the scene due to the isolation of

the property.

In the context of farm tortures in South Africa, the focus appears to be more on

the creation of terror and fear within the population than on obtaining information,

as will be evident from this report.

It should be noted that, historically, there has been political tension between

South African farmers and South Africa’s ruling African National Congress

(ANC). Portions of minority communities believe that farm tortures carry with

them an element of revenge on the white population as a result of South Af-

5 Davis, M. 2005. The Moral Justifiability of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading

Treatment, International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 19(2): 161-178.

rica’s history of racial segregation. Many believe that there is also a political

element, as the military wing of the African National Congress6 historically

defined farms as ‘legitimate ware zones’ in which soft targets could also be

attacked and killed.7 Farmers are still frequently the targets of verbal political

attacks by senior members of the ruling party. Furthermore, AfriForum recently

filed a complaint of hate speech against the ANC for its continued use of the

so-called struggle song, entitled Shoot the Boer.8 Another popular struggle

song entitled Kill the Boer, kill the farmer was declared to be hate speech by

the South African Human Rights Commission in 2003.9

6 Currently the ruling party in South Africa.

7 At the ANC General Conference in Kabwe, Zambia in 1985, a resolution was adopted that

soft targets could be killed during actions of armed struggle.

8 See AfriForum v Malema (2011).

9 See Freedom Front v South African Human Rights Commission (2003).

10 Johan Burger ‘From Rural Protection to Rural Safety: How government changed its priorities’

in Report by the Solidarity Research Institute An overview of farm attacks in South

Africa and the potential impact thereof on society November 2012, page 62.

11 Boere het meer risiko’s as polisie Beeld, 24 October 2013.

5. The extent of farm attacks in South Africa

When the South African government made a decision to deprioritise farm murders

in 2007 (see The deprioritisation of farm attacks in South Africa later in this

report), its own commission of enquiry found that at least 6 122 farm attacks

and 1 254 farm murders had taken place between 1991 and 2001. The rate at

which farm murders were committed more than doubled from 1991 to 1998.

Since 2007 no official statistics on farm murders have been made available and

it is left to civil society to compile statistics. In the same year that the government

decided to deprioritise farm murders, murders on commercial farmers

(excluding their families and employees) were calculated at 98,8/100 000. That

was more than three times higher than the general South African murder rate

and fourteen times higher than the world average.10

During 2011 the murder rate on police officers was calculated at 51/100 000,

half the murder rate on farmers four years previously. In contrast to the situation

with farmers, the government’s reaction to this issue was to organise a national

conference and formulate a counter-strategy.

During 2013 the murder rate on farms was recalculated by the South African

Institute for Security Studies (ISS). Using newer data, the rate at which South

African farmers were murdered annually was estimated at 120/100 000.11

6. The characteristics of farm attacks

Some attacks are more organised and planned than others, like with

any other crime. Firearms, tools to break into a house, wire or cables

used to restrain victims or a getaway car brought with the perpetrators

to the targeted property indicate the offender’s intent in premeditating

and planning the attack in advance.

Perpetrators who have already selected their target often stake out

the property weeks in advance, sometimes trying to gather information

from farm labourers about the comings and goings at the homestead

and the general layout of the farm and the house.

There is usually more than one attacker committing the crimes. Having

someone to work with, restrain victims, collect the loot or keep

watch allows the attack to be completed in a shorter time period.

There are cases where at least one of the attackers was known to the

victim, in other cases the attackers were complete strangers.

The initial contact with the victim can occur in various ways. Some

attackers ambush their victims by either waiting or hiding inside their

homes or at the farm gates to overpower the unsuspecting victims

arriving home. Others surprise the victims inside their homes by gaining

access to the home through windows, or confront them somewhere

else on the property. Attackers may also lure the victims outside

the house on the pretence of buying cattle or products, looking

for a job or even by setting the grass outside the home alight. This

allows the attacker to overpower the victims, leaving them powerless

and with phones or firearms out of reach.

In November 2012 the Solidarity Research Institute compiled a report entitled

An overview of farm attacks in South Africa and the potential impact thereof on

society .12 The report included the characteristics of a farm attack, which provided

an overview of the nature of an attack and what it may include. The following

factors and characteristics were identified as predominant in farm attacks 13:

12 The full report was published in the second edition of Treurgrond, published by Kraal

Publishers.

13 Claasen, L. 2012. The significance of the level of brutality and overkill in An Overview of

Farm Attacks in South Africa and the potential impact thereof on society.

The victims of the attacks are not limited to the farmer and their

spouse or family but also include domestic workers and farm labourers.

Most victims are overpowered, assaulted and restrained upon

initial contact with the attackers. There are cases where the victims

fought back in self-defence, often shooting the perpetrators and

causing them to flee.

Victims are mostly restrained with shoe laces, telephone wires or

electric cables tied around their hands and legs.

Victims may be harmed with various objects during attacks. Attackers

assault victims with steel pipes, pangas14 , axes, knobkerries15 ,

shovels, pitchforks, broomsticks and knives, or by kicking, beating,

slapping and hitting the victims.

Victims are often threatened in order to gather information about

the whereabouts of the safe, the keys to the safe and the location of

money, firearms and other valuables. Threatening to kill them or their

spouses or cause them serious physical harm, or pouring methylated

spirits over the victims may force the victims to give the information

that the attackers demand.

Various victims are horrifically tortured by pulling out their nails, pouring

boiling water over their bodies, burning them with electric irons,

breaking their fingers, pulling them behind a moving vehicle, or repeatedly

hitting them with objects before they are ultimately murdered.

The attackers ransack the house, looking for valuables and loot.

Female victims are sometimes raped during the attack.

Victims are shot, sometimes fatally, when they try to resist the attack,

try to defend their families, shoot at the attackers and much too often

for no apparent reason at all.

The attacker’s loot may, if anything, include firearms, money, vehicles,

jewellery, electronic devices, clothes, shoes or farming equipment.

Attackers either flee the scene on foot, in a getaway car ready for the

escape or in the farmer’s own vehicles. It is concerning that in numerous

cases the vehicle stolen is left abandoned a short distance from

the farm or property where the attack occurred.

14 Panga is a South African term used for a machete-like tool.

15 A knobkerrie is typically a traditional weapon used for hunting or for clubbing an enemy’s

head. It typically consists of a wooden stick with a large knob on the one end.

7. The deprioritisation of farm murders

A significant problem in determining the extent of farm murders is the fact that the South

African government, and the department of police in particular, is refusing to release any

statistics on this crime.

The government says it seems as if farmers are being targeted in

a unique manner in violent and murderous attacks. Statistics on

farm murders are released annually and the government appoints

a task team to draft a plan against farm attacks.

President Thabo Mbeki announces that the commando system

(which focuses primarily on protecting farmers) is being abolished.

Mbeki undertakes to replace the commando system by a structure

that is controlled by the police. However, this never happens.

Farm attacks increase by almost 25%. The government announces

that no further statistics on farm attacks or murders will be released.

Despite this increase and the government’s earlier undertakings farm

murders are no longer a priority.

A victim whose father and brother were murdered on their farm in the

past month submits a volume to the office of the minister. The volume

contains letters from 100 victims of farm attacks and requests the prioritisation

of farm murders. The minister responds to this by calling the

victims’ attempt to communicate with him a publicity stunt that should

not be taken seriously.17

AfriForum releases a report indicating that farm murders are not investigated

by the police with the necessary seriousness.18 The minister’s

spokesperson calls the report racist and indicates that the minister will

not read it.

Where the government admitted in the past that farmer murders are particularly

savage and that it is a crisis that should be addressed, the magnitude of the crisis is

to a great extent denied today. The irony is that the government’s reaction to farm

murders has declined as rapidly as the magnitude of the problem has increased.

The Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure

Priority Committee is appointed to handle rural

safety as a national priority.

A committee of enquiry on farm murders

is appointed by the government.

The department of police prohibits victims whose relatives were murdered

on farms from holding a protest march to its offices. AfriForum

representatives are blackmailed by a representative of the minister. A

complaint is submitted to the Public Protector (PP).16

The high court gives permission for the march to continue. The

march takes place on 1 December, but the minister refuses to accept

the memorandum and the police fail to delegate officers to regulate

traffic and ensure the safety of the marchers.

16 More information is available from AfriForum on request.

17 The full statement by the office of the minster of police is available from AfriForum

on request.

18 The full report, highlighting police negligence with respect to the investigation of

farm murders, is available from AfriForum on request.

8. The lasting effects of torture

Torture undoubtedly leaves severe physical and emotional scars if the victim

survives. This also applies to the family of the victim. Witnessing the scene of

the crime or the injuries inflicted on a loved one may leave a person severely

traumatised, racked with guilt about not being able to help or save the victim,

and overwhelmed by the aftermath of the crimes committed. Dealing with or

handling farm activities and duties for which the victim may have been responsible

puts enormous pressure on the family and friends left behind.

Victims and their families may be subjected to severe emotional stress and

trauma by having to recount events to the police or for insurance purposes.

The inability to cope with the aftermath may lead to depression, anxiety, substance

abuse and thoughts of suicide. Withdrawing from friends and family,

from daily farm duties and responsibilities and constantly living in fear of

re-victimisation may leave victims and their families in desperate need of the

necessary assistance and guidance to adapt to their changed lives.

Even though we cannot bring loved ones back or remove physical and emotional

scars and pain, AfriForum aims to help the victims and their families left

behind. By providing assistance and attending to basic needs and by providing

support wherever we can, we can use that same moral fibre mentioned earlier

to do good, to help and to support those left behind.

Ultimately the effects of experiencing such a violent event and being tortured

are far-reaching and incomprehensible. In an attempt to explain further, Bennoune

wrote the following in an article entitled Terror/Torture19 :

‘The similarities between the practices of terror and torture are

significant and defining. These include the visitation of severe pain

on victims, the intentionality of doing so, and the tremendous

fear deliberately provoked in victims, survivors and those around

them. Terrorism and torture both share some characteristics with

19 Bennoune, K. 2008. Terror/Torture. Berkeley Journal of International Law, 26:1-61.

hate crimes. Both torture and terror involve the infliction of extreme

suffering, often on a victim chosen on a basis which may include

discriminatory motives, often with a message intended for a broad

audience and meant to impact the lives of many…

‘… Ultimately, the concrete results of what is called torture and what

is called terrorism are often experienced as much the same: the devastation

of the bodies and minds of those targeted by these practices;

grave physical and psychological injury to many with profound

and lasting sequelae for survivors, some of which may be invisible to

the eye; and the spread of fear among many others of falling victim

to the same fate.’

20Roughly the equivalent of 23,68 US dollars or 129,57 Danish krone.

Steps that the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims can take:

1. Acknowledge of the crisis

2. Further engage with AfriForum and other role players about

the crisis

3. Initiate a fact-finding mission to South Africa

4. Communicate with the South African government about the

problem

5. Assist AfriForum regarding the support of torture victims in

South Africa

10. Conclusion

The horror experienced during farm tortures is almost incomprehensible. The

well-known ‘blood sisters’ from the South African company Crimescene-cleanup

have rightly indicated that, in their experience, farm tortures are by far the most

horrific acts of violence in South Africa. They are of the opinion that the term

‘farm murders’ is misleading and that the terms ‘farm terror’ and ‘farm tortures’

are more suitable.

Although there are many aspects to the farm attacks, a matter of particular

concern is the romanticising of violence towards white farmers in particular by

high-profile politicians, combined with a large degree of denial about the true

extent of the problem.

The fact that the South African government has effectively deprioritised farm

attacks, despite the increase in this phenomenon, is probably the greatest cause

for concern.

Given the complexity of the matter, the reality is that there is no silver bullet and

that this phenomenon cannot be solved with one single action. A multifaceted

approach should be followed.

Steps that AfriForum will take:

1. Conduct further research on the topic with experts in the field

2. Communicate further with the IRCT

3. Engage further with the South African Police Service

4. Launch a national awareness campaign regarding the safety of farmers

5. With the assistance of the IRCT, establish a network to support victims

of farm tortures more efficiently

https://www.afriforum.co.za/wp-content/uploads/Afriforum_Plaasmoord-verslag_Junie-2014.pdf