Instead of coming up with ideas to solve the country’s problems, politicians are relying on division and rage

South Africans are angry people. That’s what I’m told as I travel up East Africa, on my way from Johannesburg to Russia. And as my motorcycle consumes the kilometres, I’ve been wondering about our acidic and insular political discourse.

The doctors, medical researchers, artists, environmentalists and political activists I have met from Botswana to Kenya seem to know more about our politics than we know of theirs.

A lot more.

People keep asking me about President Jacob Zuma and the ANC, sometimes through the lens of tribalism. When I try to explain our politics and the various factions within the ANC — the nationalist, capitalist, socialist, black consciousness, religious, traditional, progressive and plain-out corrupt wings of the party — my explanations are beginning to sound strange. Discordant even.

What is our politics? From the perspective of being outside SA but within Africa, I can’t help but thinking what we have is the politics of hate.

EFF leader Julius Malema stirred up old division between Indians and blacks. The ANC blatantly played the race card in the last election. King Goodwill Zwelithini helped to set in motion another spasm of xenophobic violence in 2015 and recently took a dig at the Constitution, which apparently is unfair and anti-African.

Two weeks ago, and after too much konyagi, a hazardous gin-like substance strangely popular in Tanzania, I somehow ended up at a house party in Iringa.

A Tanzanian asked me where I was from. Maybe, he thought, Germany?

When I said SA, he went, “Oh, you are one of us.”

Us. I don’t often hear that back home.

Race matters in SA. You don’t have to be all that old to remember states of emergency. Economic inequalities between different races remain stark. Political parties gain support from particular ethnic groups: when South Africans enter the voting booth, racism flourishes.

Let’s face it. In many ways, apartheid is still alive. And the idea that in 1994 we’d all hold hands and sing We are the World under a great big rainbow was a bit naive.

History also helps to give a partial explanation of SA’s you-versus-me mentality. We had war between Inkatha and the ANC, in KwaZulu-Natal and on the highveld. We had all those bantustans, askaris and violence between the black consciousness movement and the ANC.

Peering back a little further, there is the credible theory that we are an unnatural country. SA did not exist before 1910. The British threw together formerly independent African kingdoms, Afrikaner republics and its colonies into a single political entity. Like many other African countries, our borders are the product of Lee-Enfield rifles and old boys from Eton.

Going way back, there is even the displacement of the San by Bantu-speaking people immigrating from the north.

So is the history of conflict and the forced amalgamation of different ethnic groups into one country a complete explanation for our politics of hate?

While not everything is rosy in Tanzania … it seems to have been able to transform different cultural and religious identities into a national identity

Looking at other African countries seems to indicate they are not. Namibia’s recent past is a catalogue of war, bodies tied to the front of Casspirs, repression, colonial borders and occupation. The Germans committed genocide on the Herero and Nama peoples, driving them out into the desert to die in 1904. If that was not enough, the Germans threw the survivors into concentration camps.

Yet, and despite having problems, Namibia does not seem to have our bitter discourse.

Tanzania provides another counterexample: in 1964 under the leadership of Julius Nyerere, Tanganyika and Zanzibar were combined to form Tanzania. To paraphrase a Tanzanian I met in Arusha, Nyerere took two countries and formed a nation.

While not everything is rosy in Tanzania — what country is all green fields filled with milk and honey? — it seems to have been able to transform different cultural and religious identities into a national identity.

So much for the theory that our history of repression and being an unnatural country are enough to explain our angry political and social discourse. So what is going on?

Our politicians have either run out of ideas or are too lazy to think of new ones. The best the EFF can do is waffle on about the nationalisation of mines and land redistribution. Perhaps the commander-in-chief should crack open a history book and read about Nyerere’s disastrous African socialism.

The DA and the ANC continue to endorse the National Development Plan (NDP), which is a pipe dream. The NDP requires strong economic growth, somewhere around 5.4%. A GDP growth rate of 1.1% isn’t going to cut it.

We hear very little about concrete plans to solve social issues such as crime and child abuse. The only response to our continuing education crisis is to lower the pass rate. Waste-water treatment, secondary road maintenance, housing and the state of our environment are all forgotten topics as far as our politicians are concerned.

Why? There has been a systematic failure to solve these problems and it is as though our leaders have given up.

Instead of laying out detailed policies for real change and development, our politicians have reached out for an old and dangerous kind of politics.

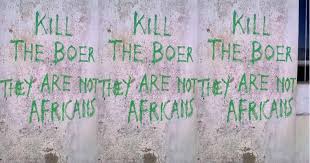

Division and hatred have replaced the debate of ideas.

Foreigners have taken all our jobs, let’s burn them. White people control the country, let’s drive them into the sea.

Indians, whites and coloureds need to stand together under a great blue banner and fight back against the black horde. You see, I told you, this is what happens when blacks run the country. Look at Zimbabwe. Why are they so stupid to vote for the ANC?

Gays, lesbians and atheists are wickedly undermining the social fabric.

As if the above was not enough, Zuma has been more than willing to reignite the old scourge of tribalism — 100% Zulu boy and all of that.

And because of our history and colonial borders, the politics of hate finds fertile ground. Our politicians are allowing old divisions to propagate for their own short-term political gains.

The national discourse has become an echo chamber where angry name-calling has replaced rational debate on how best to fix the country.

Africa has much to teach us. We can learn from Tanzania’s effort to create a national identity. Kenya’s historical and current politics should warn us of the dangers of tribalism.

But at the moment, the only thing we can teach countries north of the border is how to blow the very real chance of becoming a developed nation.

• Taylor is a postdoctoral fellow in philosophy at Stellenbosch University.

https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2017-10-13-sa–where-hating-is-easier-than-thinking/