– Read the shocking report

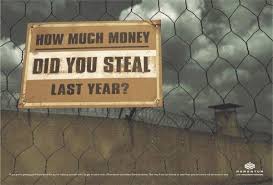

‘While corruption is widespread at all levels and is undermining development, state capture is a far greater, systemic threat’

This is an extract from:

BETRAYAL OF THE PROMISE: HOW SOUTH AFRICA IS BEING STOLEN May 2017

State Capacity Research Project Convenor: Mark Swilling

Authors Professor Haroon Bhorat (Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town)

Dr Mbongiseni Buthelezi (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand)

Professor Ivor Chipkin (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand)

Sikhulekile Duma (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University)

Lumkile Mondi (Department of Economics, University of the Witwatersrand)

Dr Camaren Peter (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University)

Professor Mzukisi Qobo (member of South African research Chair programme on African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, University of Johannesburg),

Professor Mark Swilling (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University),

Hannah Friedenstein (independent journalist – pseudonym)

Introduction

It is now clear that while the ideological focus of the ANC is ‘radical economic transformation’, in practice Jacob Zuma’s presidency is aimed at repurposing state institutions to consolidate the Zuma-centred power elite. Whereas the former appears to be a legitimate long-term vision to structurally transform South Africa’s economy to eradicate poverty and reduce inequality and unemployment, the latter – popularly referred to as ‘state capture’ – threatens the viability of the state institutions that need to deliver on this longterm vision.

Until recently, the decomposition of South African state institutions has been blamed on corruption, but we must now recognise that the problem goes well beyond this. Corruption normally refers to a condition where public officials pursue private ends using public means. While corruption is widespread at all levels and is undermining development, state capture is a far greater, systemic threat. It is akin to a silent coup and must, therefore, be understood as a political project that is given a cover of legitimacy by the vision of radical economic transformation.

The March 2017 Cabinet reshuffle was confirmation of this silent coup; it was the first Cabinet reshuffle that took place without the full prior support of the governing party. This moves the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state that emerged after the African National Conference (ANC) Polokwane conference in 2007 into a new phase. The reappointment of Brian Molefe as Eskom’s chief executive officer (CEO) a few weeks later in defiance of the ANC confirms this trend.

While it is obvious that the highly unequal South African economy needs to be thoroughly transformed, the task now is to expose and analyse how a Zuma-centred power elite has managed to capture key state institutions to repurpose them in ways that subvert the constitutional and legal framework established after 1994. As will be argued in this report, it is now clear that the nature of the state that is emerging – a blending of constitutional and shadow forms – will be incapable of driving genuine development programmes. By its very nature this mode of governance is counter development. The need for radical economic transformation must be rescued from a political project that uses it to mask the narrow ambitions of a power elite that is only really interested in controlling access to rents and retaining political power.

The dawn of democracy in 1994 delivered a promise that united South Africa. Nelson Mandela’s inauguration on 10 May 1994 expressed this promise in the clearest terms. Speaking on behalf of the democratically elected ANC-led government, he promised:

…to liberate all our people from the continuing bondage of poverty, deprivation, suffering, gender and other discrimination … [to] build [a] society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity – a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.

To deliver on this founding promise, the ANC needed to use the state institutions it inherited from the apartheid era. These institutions included national, provincial and local-level government administrations, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the judiciary, parliament and the executive.

Unsurprisingly, transforming the core administrations and SOEs into vehicles for service delivery and development became a major challenge. Undertaking deep institutional reforms is a daunting exercise that requires extraordinary levels of dedication, technical capacity and a well-defined governance programme aimed at systematically overcoming the complex legacy of apartheid. Although significant progress was made, there is now widespread dissatisfaction across society and within the ANC itself with the performance of these institutions. Whereas the promise of 1994 was to build a state that would serve the public good, the evidence suggests that our state institutions are being repurposed to serve the private accumulation interests of a small powerful elite. The deepening of the corrosive culture of corruption within the state, and the opening of spaces for grafting a shadow state onto the existing constitutional state, has brought the transformation programme to a halt, and refocused energies on private accumulation.

The then Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s State of Capture report,4 existing and growing empirical evidence (much of it referred to in this report), declarations by senior ANC members of bribery attempts, well-known sophisticated forms of bribery via ‘donations’ by businesses to the ANC, the perversion of corporate governance norms in SOEs, the resultant slow collapse of the Tripartite Alliance (the ANC, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party) and much else, have all made it clear that the 2012 National Development Plan’s recommendation that “South Africa needs to focus relentlessly on building a professional public service and a capable state”5 has been usurped.

Instead of the plan’s vision of a “professional public service and a capable state”, a symbiotic relationship has emerged between a constitutional state with clear rules and laws, and a shadow state comprising well-organised clientelistic and patronage networks that facilitate corruption and enrichment of a small power elite. The latter feeds off the former in ways that sap vitality from formal institutions and leave them empty shells incapable of executing their responsibilities.

This detailed report will provide the evidence that the nation needs to realise that the time has come to defend the founding promise of democracy and development

What this power elite cannot achieve via the constitutional state, it achieves via the shadow state and vice versa. Some senior officials and politicians have participated unwittingly in this hegemonic project because they are insufficiently aware of how their specific actions contribute to the wider process of systemic betrayal that has up until now remained opaque.

This detailed report will provide the evidence that the nation needs to realise that the time has come to defend the founding promise of democracy and development by doing all that is necessary to stop the systemic and institutionalised process of betrayal that is now in its final stage of execution. It is not too late. The 1994 democratic promise remains an achievable goal.

An analysis is required that proceeds on two levels:

1. Firstly, we must understand what the Zuma-centred power elite has attempted to achieve on its own terms, and why Zuma continues to enjoy the support of a political coalition that ensures he remains in power as the lead exponent of radical economic transformation.

2. Secondly, it is necessary to demonstrate empirically (based on public reports) how state institutions have been captured and repurposed, and why this will make radical economic transformation unrealisable if the Zuma-centred power elite remains in place.

Key terms

The aim of state capture is to change the formal and informal rules of the game, legitimise them and select the players allowed to play

Corruption and state capture:Corruption tends to be anß individual action that occurs in exceptional cases, facilitated by a loose network of corrupt players. It is somewhat informally organised, fragmented and opportunistic. State capture is systemic and well-organised by people with established relations. It involves repeated transactions, often on an increasing scale. The focus is not on small-scale looting, but on accessing and redirecting rents away from their intended targets into private hands. To succeed, this needs high-level political protection, including from law enforcement agencies, intense loyalty and a climate of fear; and competitors need to be eliminated. The aim is not to bypass rules to get away with corrupt behaviour. That is, the term corruption obscures the politics that frequently informs these processes, treating it as a moral or cultural pathology. Yet, corruption, as is often the case in South Africa, is frequently the result of a political conviction that the formal ‘rules of the game’ are rigged against specific constituencies and that it is therefore legitimate to break them.

The aim of state capture is to change the formal and informal rules of the game, legitimise them and select the players allowed to play.

Repurposing: Repurposing state institutions refers to theß organised process of reconfiguring the way in which a given state institution is structured, governed, managed and funded so that it serves a purpose different to its formal mandate.

Understanding state capture purely as a vehicle for looting does not explain the full extent of the political project that enables it.

Institutions are captured for a purpose beyond looting. They are repurposed for looting as well as for consolidating political power to ensure longer-term survival, the maintenance of a political coalition, and its validation by an ideology that masks private enrichment by reference to public benefit.

Rents and rent seeking: Development is a process that isß consciously instigated when states adopt policies to directly and/or indirectly reallocate resources to redress the wrongs of the past and to create modern transformed industrialised economies that can support the wellbeing of society. To achieve this, state institutions must be used to allocate resources from one group to another, or to support one group to overcome the disadvantages of the past. These allocations are what can be called beneficial rents. Once measures are taken, however, that result in a flow of potentially beneficial rents to specific economic actors (whether these are businesses, households or public institutions), there is competition to access these flows and this creates the conditions for rent seeking.

Centralised rent management can, of course, also be corrupted by power elites who use centralisation to eliminate lower-level competitors

There is legal, ethical rent seeking, such as lobbying or legal interventions to benefit certain groups. Rent seeking can also be corrupt, however, and lead to state capture and repurposing. Corrupt rent-seeking behaviour can undermine the development agenda by diverting resources into the hands of unproductive elites.

It follows that if beneficial rents are necessary for realising development, a system is needed to counteract the inevitable competition to access them from being corrupted by those who gain leverage via political access, passing of bribes, promises of future returns, etc.

The literature on neopatrimonialism clearly provides examples of countries that did manage to accelerate development by effectively deploying beneficial rents to boost specific economic actors.

Limiting corruption was a key part of these programmes. The most successful ones tended to be guided by a long-term developmental vision and tended to centralise control of rents to limit overly competitive destructive rent seeking. They never eliminated corruption, but they prevented it from corroding the development process. Centralised rent management can, of course, also be corrupted by power elites who use centralisation to eliminate lower-level competitors to further enrich themselves and entrench their power positions.

The power elite exercises its influence both through formal and

informal means. However, what unites the power elite is the

desire to manage effectively the symbiotic relationship between

the constitutional and shadow states

Power elite: We use the notion of a ‘power elite’ to referß to a relatively well-structured network of people located in government, state institutions, SOEs, private businesses, security agencies, traditional leaders, family networks and the governing party. The defining feature of membership of this group is direct (and even indirect) access (either consistently or intermittently) to the inner sanctum of power to influence decisions. It is not a ruling class per se, although it can see itself as acting in the interests of an existing class or, as in the South African case, a new black business class in the making. Nor is it just the political-bureaucratic leadership of the state, which is too fragmented to reliably mount a political project. The power elite is not necessarily directed by a strong strategic centre, and it includes groups that are to some extent competing for access to the inner sanctum and the opportunity to control rents.

The power elite exercises its influence both through formal and informal means. However, what unites the power elite is the desire to manage effectively the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional and shadow states. In order to do this, and in broad terms, this power elite loosely organises itself around a “patron or strongman”, who has direct access to resources, under whom a layer of “elites” forms who dispense the patronage, which is then managed by another layer of “brokers or middlemen”.

Symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state: Drawing on the well-developed literature on neopatrimonialism, we will refer to the emergence of a symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state. The constitutional state refers to the formalised constitutional, legislative and jurisprudential framework of rules that governs what government and state institutions can and cannot do.

The shadow state refers to the networks of relationships that cross-cut and bind together a specific group of people who need to act together for whatever reason in secretive ways so that they can either effectively hide, actively deny or consciously ‘not know’ that which contradicts their formal roles in the constitutional state. This is a world where deniability is valued, culpability is distributed (though indispensability is not taken for granted) and where trust is maintained through mutually binding fear. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the shadow state is not only the space for extra-legal action facilitated by criminal networks, but also where key security and intelligence actions are coordinated. As extralegal activity becomes more important, ensuring a compliant security and intelligence apparatus becomes a key priority.

What matters is the symbiosis between the two, which is what the rent-seeking power elite emerges to achieve. The symbiosis that binds the power elite consists of the transactions between those located within the constitutional state and those located outside the constitutional state who have been granted preferential access via these networks to the decision-making processes within the constitutional state. These networks have their own rules and logics that endow key players within the networks with the authority to influence decisions, allocate resources and appoint key personnel. They draw on informal power that is linked to Zuma as both the party leader and president of the country. Invariably, there are a range of power nodes spread out across the networks.

The Gupta and Zuma families (popularly referred to as the ‘Zuptas’) comprise the most powerful node, which enables them to determine for now how the networks operate and who has access. They depend on a range of secondary nodes clustered around key individuals in state departments, SOEs and regulatory agencies. In practice, this symbiosis is highly unstable, crisis-prone and therefore very difficult to consolidate in a relatively open democracy, as still exists in South Africa. It is much easier to consolidate in more authoritarian environments like Russia, which is why this kind of neopatrimonialism can quite easily drift into authoritarianism to consolidate the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional and shadow state thus reinforcing the current political crisis we face in South Africa.

Radical economic transformation: We agree that althoughß the official ANC ideology of radical economic transformation is ill-defined and lacks a discernible conceptual framework, this transformation is needed if the 1994 promise is to be realised.

Too little has been done to this end since 1994. Because the notion of radical economic transformation, however, is apparently used to mask a political project that enriches the few, subverts South Africa’s democratic and constitutional system, weakens state institutions and expatriates capital overseas, we will attempt to make clear when using this term to differentiate between this ideological role and the real intentions of ANC policy documents. In our conclusion, we argue that a new economic consensus will be required that will entail very radical change, but without subverting the constitutional state. For radical economic transformation to become the basis for a new economic consensus, it must in practice be achieved within the existing constitutional order, and an appropriately enacted legislative framework. As we will demonstrate, contrary to what is stated in ANC policy documents, the power elite profess a commitment to radical economic transformation, but see the constitutional order and legislative framework as an obstacle to transformation.

Political project: When we argue that it is necessary to focusß on the political project of the Zuma-centred power elite, we are referring to the way power is intentionally deployed in ways that serve the interests of this power elite and are legitimised, in turn, by an ideology that is repeatedly articulated by a specific (but ever-shifting) political coalition of interests (that includes the power elite but also wider networks). We will show that the abuse of power by Zuma is what enables strategies that are aimed at promoting corrupt rent-seeking practices by preferred networks and the consolidation of power by an inner core around Zuma. Legitimated by the ideology of radical economic transformation, this comprises the political project pursued by the Zuma-centred power elite. It will be argued that it is time that the ANC reclaims this ideology from the power elite that has co-opted the term for its own political project.

To reveal the systemic betrayal associated with the Zuma presidency, this report provides:

* An analytical overview of the evolution of the Zuma-led state and how a power elite emerged that has executed the betrayal of the founding promise.

* A detailed account of the emergence of the shadow state and the key role that the Gupta networks have played as brokers.

*Insight into key governance dynamics, including the role of state guarantees, the decomposition of cabinet governance, ballooning of a politically loyal top management in the public service, deployment of shadow state loyalists onto boards of SOEs and the key role of procurement.

* A note on how state capture is organised and facilitated by the Gupta networks and sanctioned by the power elite.

*A concluding section that draws out the implications for the future of state capacity and how to best defend the founding promise.

This report will be followed with a succession of detailed case studies over the coming months that will elucidate in greater detail the examples summarised in this report. These case studies will provide further evidence of a power elite that has pursued a strategy of systemic betrayal to seize control of key state institutions. The consequences and implications with respect to each case will be carefully described.

Understanding the political project

Commentators, opposition groups and ordinary South Africans underestimate Jacob Zuma, not simply because he is more brazen, wily and brutal than they expect, but because they reduce him to caricature. They conceive of Zuma and his allies as a criminal network that has captured the state. This approach, which is unfortunately dominant, obscures the existence of a political project at work to repurpose state institutions to suit a constellation of rent-seeking networks that have constructed and now span the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional and shadow state. It is being pursued in the context of two, related transitions:

1. The transition from traditional black economic empowerment (BEE), which was premised on the possibility of reforming the white-dominated economy (now depicted as white monopoly capital), to radical economic transformation, which is driven by transactors disguised as a black capitalist class not dependent on white monopoly capital.

2. The transition from acceptance of the constitutional settlement and the ‘rules of the game’ to a repurposing of state institutions that is achieved, in part, by breaking the rules.

These two transitions fuse in the strategic shift in focus from reforming the economy (the focus of the Mbeki era (1999–2008), which we call the constitutional transformers, to repurposing state institutions (with special reference to procurement and SOEs) as the centrepiece of a new symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state, which we call the radical reformers.

The ‘Polokwane moment’

The scholarly literature on South Africa’s transition notes that the betrayal of the democratic transition starts early on. The jettisoning of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) in 1996 in favour of the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy marked a profound shift away from the RDP model of development that sought to reconcile participatory democracy with state-led development to a model of development that sought welfare receipts from a growing capitalist economy. The first drew on an impressive tradition of radical politics and scholarship showing the complicity of the capitalist sector in the emergence of apartheid. The second married welfarism, market-oriented policies and the racial transformation of economic ownership and control.

The first was deeply sceptical of the ability of the capitalist sector, even in a growing economy, to generate developmental outcomes.

The second was a bet that it could.

Developmental welfarism started during the Mandela presidency (1994–1999), though its specific institutional form took shape during the Mbeki era. It was organised around three policy platforms and an organisational shift:

*Massive expansion of the grants system for the poor and the unemployed, focusing principally on mothers and the aged.

*A strong focus on ‘deracialising’ control of the economy through affirmative action policies designed to fast-track the placement of black people into management and senior management positions.

*Transformation of white ownership of the economy through BEE policies.

Mbeki’s fourth innovation was the organizational shift of political control away from the ANC itself to the Presidency – an institution that he sought to build into a powerful apparatus of control and coordination at the centre of the state. These actions were to support the aspiration of creating a South African version of the developmental state.

The 2007 ‘Polokwane moment’ when Mbeki was unseated as President of the ANC is often said to be the revenge of Luthuli House against Mbeki’s bonapartism. The party re-established control of the state by recalling a sitting state president and installing a temporary replacement until the conditions were in place for Zuma to become president. Reflecting Zuma’s commitment to the party branches, in his final address to the 52nd ANC National Conference he noted that “ANC branches are supreme”.

The ‘Polokwane moment’ represented a three-pronged reaction to Mbeki’s approach:

– The shift in power from Luthuli House to the Presidency was resented, particularly by provincial party bosses. – Black business was unhappy with an approach that hitched their accumulation potential to the commitments of white business and wanted more state support for black business. – Radical factions resented the accommodation of business and limited nature of state intervention.

During his years as president, Mbeki’s pragmatic approach to business was to engage CEOs via ‘working groups’. Zuma’s election created the conditions that resulted in the rise of the SOEs and preferential procurement as the primary means for creating a powerful black business class. At first, this was welcomed by the radical factions who interpreted this as a commitment to enhanced state intervention. But the Polokwane conference represented more than this. It was based on a conviction about the nature of economic change in a society where the African majority remain subordinated to white interests.

An Africanist conviction

At least since the historic Morogoro conference in 1969 the position of the ANC has been that the anti-apartheid struggle was a nationalist struggle led by the working class. The ANC said then that “the main content of the present stage of the South African revolution is the national liberation of the largest and most oppressed group – the African people.”

In the 1969 text this was a strategic consideration, tempered by the fact that if Africans could deliver political freedom, it was the increasingly organised working class that would deliver economic freedom. The relationship between these ‘phases’ of the ‘national democratic revolution’ have defined the terms of political struggle within the ANC and its alliance with Cosatu and the South African Communist Party ever since.

There were signs of a shift at the 1985 ANC conference in Kabwe. For all its analysis of the South African ‘social formation’ as capitalist and its identification of the ‘ruling class’ as made up of white monopoly capitalists there was no mention of the working class as a protagonist of change. The ANC has struggled with this question of who the ‘motive forces’ of the national democratic revolution are – the working class or Africans? During Mbeki’s era, the answer was the latter in his famous ‘I am an African’ speech.

The challenge, however, is that it was neither Africans as a whole nor the working class per se that benefited most during the post- 1994 period.

Despite the economy growing at a rate faster than anything seen in South Africa since the 1960s due to the economic policies Mbeki promoted, black ownership of the economy remained unremarkable.

Mbeki noted this in his speech at the Polokwane conference.

Black ownership of the economy as a whole remains very low; a recent survey put black ownership of the economy at about 12 percent … If we take foreign ownership of South African-based firms into account, black ownership might be about 15 or 18 percent of local ownership. While we are progressing, our rate of progress is unacceptably low, and we cannot take our eyes off the empowerment challenge.

The problem with BEE up until at least 2007 was that white businesses – referred to as ‘white monopoly capital’ in government discourse since 2014 – could game the policy through fronting

Yet the problem was not simply the slow pace of change. The ‘Polokwane moment’ was informed by a basic conviction that the economy remained in white hands and because of this the ‘people’ did not share in the wealth of the country. When Malema as ANC Youth League leader announced the slogan of ‘Economic Freedom in Our Lifetime’ in 2010, a recall of an older slogan from the 1940s, he insisted on the promise of the Freedom Charter.

“Simply put,” he explained, “economic freedom in our lifetime means that all the economic clauses of the Freedom Charter should be realised to the fullest.”

The problem with BEE up until at least 2007 was that white businesses – referred to as ‘white monopoly capital’ in government discourse since 2014 – could game the policy through fronting, the practice of either appointing blacks to positions without decision-making authority or by bringing in ‘empowerment partners’ on terms that did not alter the balance of economic power in firms. In other words, the BEE route to transformation left white monopoly capital intact. Moreover, it had produced a small black elite, while leaving ordinary people, especially women and youth, excluded from the economy.

What was the alternative?

When Julius Malema was expelled from the ANC in 2012 and formed the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) the alternative to BEE was expressed as the need for nationalisation of the mines and land. Malema’s critique resonated with the Fanonist critique of post-colonial nationalist movements in Africa. Later, the EFF would ground its analysis in what it claimed was a reconciliation of Fanon and Marxism-Leninism. Yet within the ANC another strategy was beginning to emerge.

It was grounded on the simple conviction that the economy was transformed to the extent that the grip of white monopoly capitalism was broken, and that black people would own and control large-scale companies. The 53rd ANC National Conference held in Mangaung in 2012 set the stage for what was to emerge:

[W]e are boldly entering the second phase of the transition from apartheid colonialism to a national democratic society. This phase will be characterised by decisive action to effect economic transformation and democratic consolidation, critical both to improve the quality of life of all South Africans and to promote nation-building and social cohesion.

The Mangaung conference was preceded by the Black Business Council’s (BBC) 2012 split from Business Unity South Africa because they argued that their interests were not well represented in the organisation. After the split the BBC became the preferred business partner of government. The name of the council is misleading because it is a professional umbrella institution representing the Black Management Forum, the Association of Black Chartered Accountants, the Black Lawyers Association and the Association of Black Securities and Investment Professionals. Michael Spicer, former CEO of Business Leadership South Africa, contends that although the government formally regretted the rupture, through its funding and other material support, it was happy to support an exclusively black business organisation. The BBC also assumed a higher profile role in the delegations of business people taken on President Zuma’s international travels.

The National Empowerment Fund was used to fund the BBC in 2012 with a R3 million grant to promote black economic empowerment. The support was meant to provide an alternative voice to what was perceived by government as a marginalised group given the history of South Africa. The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) provided support amounting to R7 million for similar purposes. The first expression of the Mangaung resolution was in an announcement made by the DTI in 2014, after the BBC had lobbied Zuma. In discussion of a new programme of radical economic transformation, the DTI declared it would “create hundred Black industrialists in the next three years”, further stating that:

Over the next five years, a host of working opportunities will become available to South Africans. For example, a new generation of Black industrialists will be driving the re-industrialisation of our economy. Local procurement and increased domestic production will be at the heart of efforts to transform our economy, and will be buoyed by a government undertaking to buy 75% of goods and services from South African producers [emphasis added].

The centrepiece of the strategy was to use the state’s procurement spend to bring about radical economic transformation. This was not nationalisation, but the creation of a new black-owned economy.

The battleground for economic transformation was shifting away from the economy itself to the state and, specifically, to SOEs that outsourced massive industrial contracts to private-sector service providers. Enter Eskom, Transnet, SAA, the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA) and other SOEs as the vehicles for change.

This model required preferential procurement from black-owned companies and the displacing of white-managed and -owned businesses from SOE-linked value chains.

The problem, however, was that the existing constitutional and legislative environment constrained this model of economic transformation by insisting that bidders for state contracts satisfied more than racial conditions, namely price and experience. In other words, the blackness of firms was not a sufficient condition for securing contracts from the state. Moreover, given that white-managed and -owned businesses had more experience than emerging black companies, were better capitalised and, moreover, could bring in empowerment partners to circumvent racial conditions, it seemed that the formal rules of the game were rigged in favour of white monopoly capitalists and against blackowned businesses.

This model of economic transformation has received clearer theoretical and political articulation since then. The ANC’s policy discussion paper circulated to branches in 2017 was titled Employment Creation, Economic Growth and Structural Change.

This document uses the above cited resolution from the 53rd National Conference and the National Development Plan as a point of departure for defining radical economic transformation:

Primarily, radical economic transformation is about fundamentally changing the structure of South Africa’s economy from an exploitative exporter of raw materials, to one which is based on beneficiation and manufacturing, in which our people’s full potential can be realized. In addition to ensuring increased economic participation by black people in the commanding heights of the economy, radical economic transformation must have a mass character. A clear objective of radical economic transformation must be to reduce racial, gender and class inequalities in South Africa through ensuring more equity with regards to incomes, ownership of assets and access to economic opportunities. An effective democratic developmental state and efficiently run public services and public companies are necessary instruments for widening the reach of radical economic transformation enabling the process to touch the lives of ordinary people.

It is hard to disagree with the ambitious content of this vision for inclusive structural transformation. As an ideology, it has very broad appeal because of South Africa’s economic challenges. This ideology, however, can also cement a coalition that (largely unwittingly) enables the betrayal of this vision by a power elite who are only interested in rent seeking and political survival, and who are prepared to use extra-constitutional and unlawful means to achieve their goals where necessary.

Understanding rents and rent-seeking

Since 1994, the South African government has adopted a wide range of policies that actively seek to reallocate resources across a wide range of sectors, including such things as housing subsidies, social grants, incentives for new black-owned industries, BEE strategies, preferential procurement, investments in education, land reform and tariffs.

For neoclassical economists, these expenditures are rents that require state intervention and therefore are usually inefficient – a windfall gain for a private actor is a loss for society. Although this perspective is no longer influential, it has translated in the past into policy advice about how to ‘level the playing field’ and ensure ‘good governance’ by minimising state intervention to remove the conditions for rent seeking.

Comprehending rents and the competition

to control rent seeking is key to understanding the contemporary

political crisis

For heterodox economists, these kinds of beneficial rents are necessary during certain stages of development. State interventions such as using procurement to benefit certain groups, promoting research and development to create competitive sectors, protecting certain industries during the early phases of their development, favouring historically disadvantaged groups in various ways or subsidising certain actors/groups while they are establishing themselves are all deemed to be necessary developmentally beneficial rents if the goal is growth, development and poverty eradication.

There is reference in the economics literature to both productive and unproductive rent seeking. The former (beneficial rents) seek to achieve clearly defined transformation goals and there is an exit plan. The latter become permanently captured by interest groups who would use their political power to hold on to rents even when they no longer perform productively.

Bearing in mind the definition of rents and rent seeking provided at the start of this chapter, comprehending rents and the competition to control rent seeking is key to understanding the contemporary political crisis. As we will argue, what started off, according to our findings, as collusion in relatively low-level corruption between the Zuma family and the Guptas has evolved into state capture and the repurposing of state institutions. In less than a decade the Zuma and Gupta families have managed to position themselves as a tight partnership that coordinates a power elite that aims to manage the rent seeking that binds the symbiotically connected constitutional and shadow states. What unites this power elite is an ideological commitment to building a black business class, using state institutions to drive investment and growth, and streamlining through centralisation the control of rent seeking.

Different constituencies are attracted to different combinations of this political project, from those who simply want to be awarded SOE contracts to radicals pleased with more state intervention; from party loyalists terrified about electoral losses if the economy does not improve to a vast network of people who exchange loyalty for patronage. The resolutions of the 53rd National Conference and the 2017 ANC policy discussion document Employment Creation, Economic Growth and Structural Change capture this common purpose. But in reality, these resolutions and the 2017 policy document contradict what the Zumacentred power elite does in practice.

To understand this political project, however, it is necessary to understand the limits of the post-1994 policy framework that Mbeki himself talked about at the Polokwane Conference.

From constitutional transformers to radical reformers

A critique of South Africa’s transition to democracy has been developing for several years within mainstream ANC thinking (originating in the ANC Youth League under Malema) that has focused on the profound continuities between the apartheid and the post-apartheid economies: glaring inequality that still largely coincides with the country’s traditional racial profile. What is new about this critique is that it increasingly repudiates South Africa’s constitutional settlement as an obstacle to radical economic transformation. This has led to the current clash between radical reformers and the constitutional transformers. The former want to subvert and bypass constitutionally entrenched institutions to manage rents on behalf of a power elite, while the latter seek to build state capacity to deliver on the 1994 promise of equality and development by managing rents to promote investment and service delivery.

This difference between the radical reformers and constitutional transformers lies in how the transition to democracy is understood.

The institutions produced by this transition are associated with two different ways of doing politics. The constitutional transformers operate within the confines of the Constitution and are invested in institution building. That is, social and political transformation is deemed contingent on giving flesh to the socio-economic rights defined in the Constitution by building state administrations able to work programmatically to achieve progressive policy outcomes.

Building a capable state is their aim, including limiting corruption wherever possible. There has been much activism from social movements on this front to force municipalities and national and provincial departments to implement their own policies and/or to comply with constitutional mandates. The Socio-Economic Rights Institute and the Social Justice Coalition, for example, have been using constitutional provisions to win struggles waged by poor communities.

Starting as a revolt against Thabo Mbeki, though not yet associated with a clear ideology, the ‘Polokwane moment’ gave rise to a new power elite that found a language of its own in the narratives of the radical reformers. Its protagonists claimed to speak for ‘ordinary people’, those who are not well educated, who don’t speak English well, who live in shacks or small towns and rural areas and who are excluded from the economy and the formal institutions of the state. They constitute a politics profoundly mistrustful of the formal ‘rules of the game’, whether of the Constitution or of government.

The formal rules are rigged, this position proclaims, in favour of whites and urban elites, and against ordinary people. Radical economic transformation is thus presented as a programme that must frequently break the rules – even those of the Constitution. The argument is compelling at first glance, especially because unemployment and poverty are presented as overwhelmingly black experiences.

The constitutional transformers

For those progressive forces that negotiated the democratic breakthrough and for the many people that moved into government after 1994, the constitution was deemed a framework through which transformation could be achieved.

The Constitution was based on a complex negotiated settlement, including a deal made with major conglomerates that they would mobilise investments in the post-apartheid economy – in particular, in manufacturing – to support the democratic project. At the time, a handful of people representing the conglomerates that owned the large bulk of assets could make this deal. However, as elaborated further below, the combined impact of the shareholder value movement, financialisation, trade liberalisation (from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trades to the World Trade Organisation), BEE deals and import-dependency combined to break up these conglomerates and severely limit investment, particularly in the manufacturing sector.

International listings of South African companies promoted disinvestment rather than supporting the much-promised capital raising for inward investment

Strategic refocusing (as required by the shareholder value movement) resulted in a massive increase in returns to shareholders that, in turn, undermined reinvestment (a total of R384 billion between 1999 and 2009, equal to 17 percent of gross fixed investment during this same period). This was reinforced by transfers to BEE groups (R317 billion between 2000 and 2014 equal to 8 percent of gross fixed investment during this period). These two sets of transfers (both underestimated here because they exclude transfers to external shareholders, and are only for specific periods) created disincentives for reinvestment because of the need to service the (often debt-based) equity claims of these groups.

Debt-based buyouts of key South African manufacturers (such as the South African Iron and Steel Corporation, Dorbyl and Scaw) by local and international companies limited investment in expansion because of the need to service company debt. Furthermore, international listings of South African companies promoted disinvestment rather than supporting the much-promised capital raising for inward investment. And debt-based expansion of consumption to deracialise the middle class resulted in consumerrather than production-based growth (which largely reached its limits by the early 2000s).

As a result, South Africa continues to lag its emerging market peer group in terms of investment expenditure as a share of gross domestic product. Data for 2012 for example, shows that in China and India investment levels were between 1.8 to 2.8 times that of South Africa. Yet the interesting anomaly is that the rates of return on investment in South Africa are not low; real returns have averaged around 15 percent between 1994 and 2008 while nominal returns were 22 percent between 2005 and 2008.21 Notably these rates of return are the same as that of China, albeit over a longer period. Usually investment levels are high if returns on investment are high. Not so in South Africa. What this suggest is that nonprice factors have affected the level of investment in South Africa.

Poverty, when measured using the official national poverty line (as updated in 2011), increased from 31 percent in 1995 to 53.8 percent in 2011

These range from product and factor market distortions to structural concerns around political stability and governance. The rate of return, therefore, is not the only factor that guides and influences investment levels in an economy. Furthermore, and exacerbating the problem, South Africa’s notoriously low savings levels (fuelling our consumption-driven economic growth trajectory) means that we rely on short-term capital flows to finance domestic investment.

The dependence on short- to medium-term capital inflows tends to perpetuate dependence on the resource sector, processors of resources, and powerful, publicly-quoted oligopolies in the services sector. The market power of these companies produces the generous margins that portfolio investors seek.

The upshot is that South Africa remains dependent on short-term capital flows to finance investment focused on a narrow band of capital-intensive or highly concentrated sectors, in an environment of low-savings and high internal rates of return. The path dependency then in this job-starved, capital intensive growth trajectory is starkly evident. The most significant result of this economic conundrum is that poverty, when measured using the official national poverty line (as updated in 2011), increased from 31 percent in 1995 to 53.8 percent in 2011.

Instead of using the post-1994 moment to attack the unproductive structure of the economy (in particular the mineral-energycomplex), the constitutional transformers adopted economic policies that were inappropriate to direct the restructuring of the extractive institutions at the centre of corporate South Africa.

They assumed that a remarkably simple mix of economic policies would provide the framework for macroeconomic stabilisation and growth of a market-driven economy. These included inflation and public expenditure controls; removal of market ‘distortions’ such as tariffs, capital controls, excessive labour market protections and requirements to lend to particular sectors (to avoid inefficient rents); a faith in foreign direct investment and the associated transfers of technology and management efficiencies.

This economic cocktail was coupled to an equally simple equation of development with fiscal policy, resulting in a massive expansion in expenditures on welfare, housing, health and education.

The combination of market-oriented macroeconomic stabilisation and development-as-welfarism did not adequately address the problem and consequences of low investment levels caused by the way the South African corporate structure was being transformed by a combination of shareholder value, BEE deals and financialisation.

When Mbeki was forced to resign as president, the ANC was facing the consequences of growing inequalities, persistent poverty and remarkably high unemployment levels

Critics of the post-1994 market-oriented economic policies argued that international evidence shows that public investment does not in fact displace private investment; but instead it catalyses private investment. Furthermore, international experience shows that lowering tariffs without restructuring by using industrial policy had proven unviable in other contexts (especially where developmental rent management worked well). These critics further argued that capital account stability was a good thing; that a stable well-paid workforce was preferable to an over-indebted underemployed poorly paid workforce; and that the state needed to actively lead corporate restructuring to ensure that investment rather than dividends and rents was prioritised.

Although the adoption of the developmental state discourse in the early 2000s marked a realisation that the state needed to play a stronger leadership role in the economy, this entailed a narrow focus on infrastructure-led growth to draw in private investors rather than strategies to guide corporate restructuring and privatesector investment into strategic industrial sectors.

When Mbeki was forced to resign as president, the ANC was facing the consequences of growing inequalities, persistent poverty and remarkably high unemployment levels. This prompted the ANC Youth League to lead the way in calling for more radical economic transformation. All talk of privatising SOEs fell away as they came to be viewed as key instruments for ratcheting up investment levels in the wake of the ongoing failure of the corporate sector to adopt a long-term dividend-oriented approach to investment. At the same time, there was growing dissatisfaction in the black business sector – the slow pace of accumulation in this sector was blamed on an over-dependence on the white corporate sector.

The radical reformers

The rise of Zuma can be understood in this context. With an economic environment set by the developmental state discourse, infrastructure-led growth, BEE, the emerging significance of the SOEs and state-investment institutions like the Public Investment Corporation, conditions were ripe for an assertive power elite to repurpose state institutions in the name of addressing the contradictions of the Mbeki era. As discussed in Chapter 3, the solution of the Zuma faction was heavy dependence on the use of the procurement systems of the SOEs. Repurposing the SOEs to become the primary mechanisms for rent seeking at the interface between the constitutional and shadow state became the strategic focus of the power elite that formed around Zuma. To facilitate this, they needed brokers to help bypass regulatory controls and shift money around (through local and international financial institutions) to finance deals as well as the transformation of the ANC into a compliant legitimating political machine. The Gupta networks emerged as the anointed brokers of this expanding rent-seeking system.

Repurposing the state

Yet the politics of radical economic transformation, despite the slogan, is not focused on the economy, but on the state. This was most clearly expressed in the National Macro Organization of State (NMOS) Project launched on 4 June 2014 at a NMOS project team workshop attended by all national government departments.

Over the last 20 years the value of goods and services that

government purchases, largely from the private sector, has grown

to between R400 and R500 billion a year. This figure is testament

to the near complete outsourcing of government’s core functions

The NMOS was established to implement the new Cabinet portfolios announced on 25 May 2014 after the general election. Significantly, the NMOS steering committee, comprising all Director-Generals and chaired by the Director-General in the Presidency, reports directly to the president. The Department of Public Service and Administration (DPSA) acted as the secretariat of the NMOS project team, which reported to the steering committee. The NMOS was ostensibly about the renaming of some departments (e.g., the Department of Water Affairs to the Department of Water and Sanitation), the splitting of existing departments (e.g., the Department of Women was created from the Department of Social Development), creation of new departments (e.g., the Department of Small Business Development), transfer of functions from one department to another, and reorganisation of departments (especially those who received new functions).

The 2014 NMOS built on and reinforced the 2009 NMOS that initiated the proliferation of Cabinet portfolios. However, there was a renewed urgency in the 2014 NMOS with the Department of Government Communication and Information System insisting in its communication strategy for the NMOS that “[t]he reconfiguration of Cabinet and government departments is meant to create a capable state that will be able to implement the National Development Plan, respond to the current challenges and speed up service delivery to improve the lives of all people who live in South Africa [emphasis added]”. As this statement suggests, the emphasis was that the NMOS Project be presented as improving service delivery.

However, what ‘capable’ meant and how to ‘speed up’ service delivery was never further elaborated. All attention was focused on the operational details, specifically how many departments and who was responsible for what. By this point, Minister of Public Enterprises, Malusi Gigaba, appointed on 1 November 2010, had also taken the first steps towards repurposing the SOEs. Throughout his tenure until 2014 as public enterprises minister, Gigaba was engaged in the restructuring of SOE boards, which became broadly representative of ‘Gupta-Zuma’ interests.

Over the last 20 years the value of goods and services that government purchases, largely from the private sector, has grown to between R400 and R500 billion a year. This figure is testament to the near complete outsourcing of government’s core functions.

Ironically, as government does less, there is more and more of it – personnel, ministries, departments, agencies and entities.

Essentially government has become a massive tender-generating machine. The Public Affairs Research Institute called it a “contract state”28. This constitutes the core of what could in theory be a system for allocating beneficial rents to drive development. In reality it has provided many opportunities for entrenching clientelism and patronage networks that become dependent on the favour of those who make the decisions at the top of the pyramid.

Seen from this angle, the NMOS can be seen as a framework that enabled the knitting together of the symbiotic relationship between the formalities of bureaucratic governance in the constitutional state and the increasingly significant informal networks of the ‘shadow state’, reinforced by the Guptas as external brokers and a parallel set of increasingly compliant intelligence and policing apparatuses.

The proliferation of government departments at the national and provincial levels from 2009 onwards to extend the political patronage networks followed the decentralisation of financial accountability to departmental heads (defined as chief accounting officers). This process of decentralisation of financial accountability followed the abolition of the State Tender Board in 2000. The rationale for these financial management reforms came from the ‘new public management’ movement that became popular internationally and in South Africa (via the public management schools) during the 1990s.

Extolling the virtues of ‘steering and not rowing’, the movement depicted contracting out and decentralisation of financial accountability as institutional reforms for improving the efficiency of the public service. However, lessons from the around the world show that combining the decentralisation of financial accountability with a ballooning of the public service creates ideal conditions for a proliferation of corruption. One without the other is preferable, but together these conditions create a perfect storm. The result in South Africa was the expansion across all levels of government (national, provincial and local) of a competitive kleptocratic culture. By the 2014 election, this culture had been in place for more than a decade.

To substantiate the above argument, we analysed the fraud and corruption cases for the period 2010–2016 that relate directly to procurement by state institutions and SOEs. There were 166 cases involving amounts ranging from R70 000 to R2.1 billion. The total amount at stake for all these cases is a staggering R17 billion. However, some caution is required in understanding this figure. Not all the amounts are known for all the cases, which means it could be an underestimation. Also, the documentation we reviewed sometimes refers to the contract value and sometimes to the amount that has been fraudulently or corruptly misappropriated.

What is significant, though, is that the evidence supports the argument that fraud and corruption proliferated during the 10 years leading up to 2014, peaking in 2012.

Signalling that the power elite around Zuma was concerned about increasingly competitive and out of control corrupt practices at the lower levels, Zuma instructed then Minister of Finance Pravin Gordhan to lead an initiative to investigate Malema-linked rentseeking practices in Limpopo in 2012. Although Limpopo accounted for only 10 percent of the 166 cases analysed, the amounts involved equalled 15 percent of the total amount for all 166 cases.

With the takeover of the National Treasury now made possible

by the appointment of Malusi Gigaba as Minister of Finance,

centralisation of rent seeking to consolidate the symbiosis between the constitutional and shadow state has moved into a new implementation phase

Gordhan did more than just investigate – he shut these networks down. The political fallout from this episode (including the repercussions of the expulsion of Malema earlier that year) in the context of spreading corruption in all provinces led Zuma and other leading national figures to start calling for the re-establishment of the State Tender Board. This reflected a deeper underlying concern, not with rent seeking per se, but with the fact that there was too much rent seeking competition at the lower levels of the state that was out of control (hence the reference in the ANC 2014 Election Manifesto to the need to centralise tenders).

The Limpopo episode may not have triggered, but it certainly reinforced, what appears from the outside to be a coherent multi-pronged strategy to centralise control of rent seeking by an increasingly confident power elite. In practice, there was a guiding goal to centralise control, but this was achieved via a mish-mash of tactical decisions to exploit opportunities as they came up in opportunistic ways. The absence of strategic coherence and coordination meant there were many contradictory outcomes, mishaps, miscommunications, fall-outs and breakdowns along the way.

With the takeover of the National Treasury now made possible by the appointment of Malusi Gigaba as Minister of Finance, centralisation of rent seeking to consolidate the symbiosis between the constitutional and shadow state has moved into a new implementation phase. The increased confidence and brazenness of the Gupta networks on SOE boards and in senior management since the reshuffle confirms this.

In summary: seven broad areas of capture

The evolution in recent decades of rent management systems within neopatrimonial regimes around the world has taken many forms. In summary, though, they can be characterised within a spectrum that ranges from centralised/coordinated to chaotic. The South African rent-seeking system is a kind of hybrid, partly because of Zuma’s personally vulnerable position due to outstanding and unresolved charges against him, the Constitutional Court finding on Nkandla and his embeddedness within a well-structured constitutional order. He aspires to be like Putin or Angola’s Dos Santos, but is entangled by constitutional state requirements he cannot dispense with (like reporting to Parliament and subordination – at least for now – to the Constitutional Court) and competitive dynamics within the shadow state that the Gupta networks do not always control (witness the PRASA debacle).

The Guptas managed to position themselves as the key strategic brokers of the networks that connected the constitutional and shadow states. They began with little more than a tight connection to Zuma. Like Schabir Shaik before them, they turned this political capital of having access to the president to their advantage to secure deals in his name in return for a percentage of the contract. The inclusion of Zuma’s twin children in Oakbay companies as early as 2009 was used to full advantage. For Zuma and others around him, it was convenient to have a single clearinghouse where deals were brokered and financial transactions managed at a distance, especially if this clearinghouse was managed by non-South Africans with no loyalties to factions within the ANC. The word in black business circles was that without a deal with the Guptas, landing contracts with SOEs would be impossible.

This raises the question about whether there is in fact a strategic centre of sorts. In general, the answer is no. Nor is there one single powerful network that overrides all others. The clearest and most disturbing indicator that the South African rent-seeking system tends towards the chaotic end of the spectrum is the collapse of the cabinet system as the core of the executive branch of the state.

There is evidence that Zuma tends to govern via a set of ‘kitchen cabinets’ comprising selected groups from different networks.

Kitchen cabinets are essentially how the competing nodes within the power elite coalesce and disperse to influence decision-making

Kitchen cabinets are small informal reference groups that are convened on an as-needed basis. They can also be shell structures that are activated when needed. As will be demonstrated, they have been known to be drawn from the state security establishment, Gupta networks, SOE sector, sub-groups of cabinet ministers and deputy ministers, family networks, international networks (e.g., Angola, Russian intelligence), key black business groups, the ANC (in particular the Premier League and Magashule), and selected loyalists in the public service (usually loyal director generals).

Kitchen cabinets can be once-off consultative events (e.g., with black business), or semi-permanent structures like interministerial committees comprising people from different sectors and environments to tackle a common issue, or regular meetings with key networks (e.g., the Guptas or family networks). They are essentially how the competing nodes within the power elite coalesce and disperse to influence decision-making. Given that it is well known that those with the greatest influence are those who have spoken last to Zuma, it is unsurprising that these kitchen cabinets will lobby hard for face-time and follow-through on the deals they want to see realised. When we refer to the ‘power elite’ in this report, it is essentially key individuals located in these networks who are united by a sense that they have an historic mission to ensure the emergence of a black business class powerful enough to displace the white business class that remains a dominant force in the economy. How this reconciles with the growing prominence of Gupta-linked/owned companies with limited BEE credentials that win key contracts (e.g. T-systems or Cutting Edge at Transnet) remains somewhat of a mystery.

In summary, this power elite has centralised control within seven broad areas (some of which are elaborated in greater detail in subsequent chapters):

i. Securing control over SOEs by chronically weakening their governance and operational structures

The appointment of Gigaba on 1 November 2010 as Minister of Public Enterprises marked the start of a systematic process of reconfiguring the boards of SOEs to ensure compliance, starting with his attempt to get little known DTI official and known Gupta associate Iqbal Sharma appointed as Transnet Board Chairperson in 2011 and the successful appointment of Brian Molefe as Transnet CEO in the same year. Throughout his tenure until 2014 as Minister of Public Enterprises, Gigaba was engaged in the restructuring of SOE boards. This, however, was only the first step in the repurposing of the SOEs.

The second was to exploit the loophole in the Public Finance Management Act that made it possible to use the procurement procedures of SOEs to benefit selected contractors who had been sanctioned by the Gupta network. The loophole is that SOEs are not required to table their budgets and expenditure plans in Parliament, unlike government departments, which means they cannot be scrutinised in the same way as departmental budgets and expenditures. The details of SOE expenditure can, therefore, be hidden from public scrutiny.

ii. Securing control over the public service via, for example, NMOS

After the 2014 election, the NMOS project steering committee reported directly to the president creating the opportunity to couple political loyalty and responsibility for specific functions and associated budgets with deals to effectively manage procurement to control the rent-seeking networks.

iii. Securing access to rent-seeking opportunities by shaking down regulations

Government ministers acting in concert with private interests use regulatory instruments or policy decisions in an arbitrary manner to “shake down” incumbent businesses – including black businesses – and favour particular interests. Instead of prioritising job creation and economic growth, decisions are taken for the benefit of a particular company, faction or group. The Tegeta vs Glencore Optimum deal is an example.

iv. Securing control over the country’s fiscal sovereignty

And then, there is the National Treasury. Gordhan and the National Treasury were regarded as an obstacle to this project of centralising the management of rents. The National Treasury believed in levelling the playing field and good governance. Hence the establishment of the Chief Procurement Officer in 2013. The National Treasury were aware of and opposed the increasingly corrupted and centralised rent management system that Zuma’s power elite was setting up. It used the Financial Intelligence Centre to track illicit financial flows in ways that illuminated the workings of the shadow state. Prior to the cabinet reshuffle, the Financial Intelligence Centre was the only intelligence agency not controlled by the Zuma network. And the National Treasury controlled the Industrial Development Corporation and the Public Investment Corporation, which is the second largest investor on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Zuma’s power elite realised that to effectively centralise control of rent seeking, they needed control of the Office of the Chief Procurement Officer, the Finance Intelligence Centre, the Public Investment Corporation and the unique power available to the Minister of Finance to issue guarantees. This is only possible if a loyal Minister of Finance is in place.

v. Securing control over strategic procurement opportunities by intentionally weakening key technical institutions and formal executive processes

Momentous national decisions appear to be taken on the basis of ad-hoc political judgments, without prior consideration of the legal, financial, economic or other public policy implications. Where technical opinions contradict the plans of vested factional interests they are arguably actively suppressed or excluded from consideration. Processes are constructed in a manner that avoids deliberation on basic facts and critical evidence (see The Special Significance of the Nuclear Deal).

vi. Securing the loyalty of the security and intelligence services by appointing loyalists

Securing control of the SOE boards went in conjunction with the process of removing key people from the security and intelligence agencies. They were replaced with loyalists who were prepared to use dirty tricks and other means to deal with troublesome individuals, especially if they were key players

vii. Securing parallel government and decision-making structures that undermine the executive. This includes strengthening of the ‘Premier League’ (those with the apparent power to determine leadership positions)

There appears to be concerted efforts underway that undermine collective political institutions in the Executive, including Cabinet. It appears that critical decisions are delegated to handpicked groups, masked as Inter-Ministerial Committees, that are able to function in an unaccountable manner. Recent examples include:

– The IMC on Banks (purportedly set up to investigate the regulations and legislation that govern them, but strangely chaired by Mines Minister Mosebenzi Zwane and set up after the Bank’s closed the Gupta bank accounts);- The IMC on Communication, unusually chaired by the President; – The National Nuclear Energy Co-ordination Committee (NNEECC), chaired by President Zuma.

The nature of IMC’s is that in and of themselves they lack transparency, in that they do not report to Parliament (which individual members of Cabinet are required to do) and they are not formulated in legislation (as is the case of formal Cabinet Structures).

Additionally, a series of political appointments at Cabinet and provincial government levels reinforced the Premier League, with Ace Magashule emerging as its de facto leader. The rise of Magashule to chief political confidante of the President, with rumours that Zuma views him as the preferred candidate for vicepresident, points to the fact that since the 2014 election Zuma has come to depend increasingly on the provincial party machines represented by the Premier League.

The special significance of the nuclear deal

It is no secret that one of Zuma’s top priorities is to ensure that the nuclear deal with the Russians is finalised. Ignoring for the moment the obviously important issues that this is the most expensive form of power available, it is unaffordable now and will be more unaffordable when built due to inevitable budget overruns (as is normal in all Russian nuclear projects) and the procurement process has been illegal (as per the recent course case), what matters is that the nuclear deal has emerged from the depths of the shadow state system.

The Guptas bought their uranium mine because they assumed the nuclear deal would be done, and there is evidence that Russian intelligence has a presence in the Presidency to guide the process.

To ensure effective support for the nuclear deal, intelligence capabilities have been boosted that are now interfaced with the Gupta networks that brokered the shadow state transactions to pave the way for the nuclear deal. There are allegations that one set of transactions involved Russian funding for the local government elections, which may explain where the ANC managed to find R1 billion for this campaign.

The nuclear deal is also central to the consolidation of a new framework for radical economic transformation. If the nuclear deal is implemented, this will signify the final consolidation of Zuma’s rent-seeking system as the glue that binds together the constitutional and shadow states. It is reasonable to assume that the Russians have linked the approval of the nuclear deal to major investment initiatives in the future that could be useful for shoring up support of black business.

It is arguable, therefore, that alternative energy futures are at the heart of the South African political crisis. According to the CSIR, in 2016 the price of renewable energy was 62c/KwH over the life cycle, compared to coal which was R1.03 – R1.20/KwH and nuclear was R1.30/KwH over the life cycle.30 The CSIR estimated that the nuclear energy option could result in an increased annual cost of R90 billion compared to the cost of renewable energy. There is, therefore, no economic rationale for building nuclear power plants in South Africa. Many experts and commentators now argue that the only reason the Zuma-centred power elite push the nuclear option is because it creates an opportunity to extract rents on a massive scale while giving the Russians the strategic advantage they aim to achieve in building all their nuclear power plants. They are building nuclear power plants in 30 countries at the moment. As one commentator put it, a Russian nuclear plant is a ‘combination of an embassy and military base’ – to this one can add another advantage: they give Russia financial control of the economy if the financing was done by issuing a sovereign guarantee.

Conclusion

We must understand the politics of the power elite around Zuma in this context. The political party he heads is ideologically committed to radical economic transformation, which is to be achieved in part by using government’s procurement spend to favour black businesses. This, in turn, is the cornerstone of a strategy to displace the traditional corporates who have hitherto done little to increase gross domestic fixed investment. However, this ideology masks the repurposing of state institutions to enrich a narrow power elite.

A vacuum is created that can be filled by transactions that occur within the shadow state. This is especially devastating for working families and for the poor, who are more dependent on government services than the middle class and the rich

This sets the context for understanding Gigaba’s statements after he took office in April 2017. He made it clear that he is committed to radical economic transformation and that he does not intend depending on white monopoly capital. Now that they have control of the National Treasury via Gigaba, the power elite assumes they will have the wherewithal to centralise and control rent seeking. A key condition of success is a compliant ANC. Extracting a flow of funds via shadow state networks (such as during the PRASA deal) makes it possible to keep the ANC going, but as a giant political Ponzi scheme that legitimates what is going on by denying the existence and salience of the shadow state.

The politicisation of procurement as a means to achieve radical economic transformation frequently results in the subversion of service delivery mandates. Therefore, in recent years there have been purges of professional public servants and the repurposing of administrations away from their constitutional and legislative mandates. It has also opened departments and especially SOEs to massive competition and rivalry, not so much about policy, but about who gets what tenders. This weakens and often breaks administrations, which are then unable to deliver services. A vacuum is created that can be filled by transactions that occur within the shadow state. This is especially devastating for working families and for the poor, who are more dependent on government services than the middle class and the rich. Failures in health and education, for example, reproduce historical, racialised patterns of inequality. It distracts attention from the economy itself and the inclusive structural transformation that is needed to make the economy more productive and labour-absorptive.

Development in an unequal society cannot work without the allocation of beneficial rents. What matters is whether the rent management system is corrupted by clientilistic and patronage networks or not. Once it is corrupted, a process sets in that can lead to the hollowing out of the state, endemic conflict and economic collapse while an elite enriches itself. This cannot be allowed to happen.

https://www.businesslive.co.za/rdm/politics/2017-05-26-how-south-africa-is-being-stolen—read-the-shocking-report/