The White Settlement of Southern Africa 1652 – 1850

The establishment of White settlements in what later became South Africa and Rhodesia were different from those outposts established elsewhere in Africa during the colonial period, because it was only in Southern Africa that White numbers ever reached a large enough total for them to establish large scale settlements which seriously affected the balance of power.

The histories of South Africa and Rhodesia – the two largest White settlements, and the interrelated Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola – all serve as valuable lessons in racial dynamics and as such are well worth looking at in some detail. In South Africa, a large White population had the chance to create their own state, but failed to do so due to their reliance on Black labour, while in Rhodesia, Mozambique and Angola, no serious efforts were ever made to establish majority White occupation in any particular area, with these states only surviving as long as they did through brute force and one of the most protracted and violent race wars since the invasion of Europe by Asians and Turks nearly 1000 years earlier.

South Africa – FIRST WHITE SETTLEMENT 1652

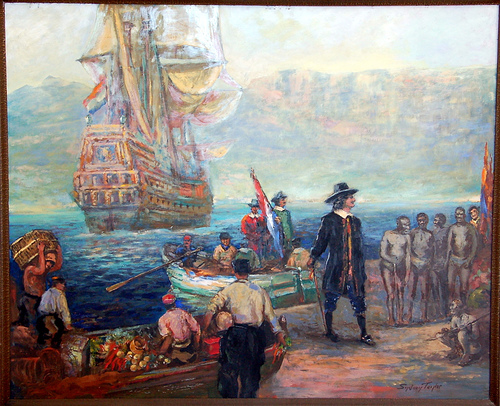

The first major permanent White settlement in Africa came in 1652, when a Dutch trading company, the Dutch East India Company sent one of its officials, Jan van Riebeeck, to what is now called Cape Town, to build a resupply station for company ships travelling to and from Asia. Around this station the first White settlement spread – and met the first non-Whites, tribes of Hottentots and Bushmen who were happy to trade cattle with the new settlers.

Above: A view of White settlers at the southern most point of Africa: Cape Town in the year 1679. Dutch ships stop for re-supply purposes on their way round Africa to the Far East. Ironically, the Dutch never intended to establish a proper colony, only a re-supply station.

First Farmers

By 1657, it became evident that the company’s farming efforts were inadequate, so a small number of company employees were released from their contracts and given uninhabited land to work as independent farmers supplying the company’s needs. The first White farmers in Southern Africa – called Free Citizens – were created. Between 1680 and 1700, the Dutch encouraged White immigration in ever increasing numbers: Dutch, Germans and French Huguenots (Protestants escaping religious persecution by Catholics in France) all started arriving, quickly filling up the region surrounding Cape Town.

Bushmen Immigrate North

Relations with the native Hottentots and Bushmen became rocky. First, their numbers were decimated by the introduction of European diseases to which they had no resistance, and then they were slowly squeezed out of the area

surrounding Cape Town. As the Hottentots and Bushmen were nomads, there was no claimed land for the White settlers to seize, but as the number of White farms increased, so the roaming space of the natives grew smaller.

The White settlers soon began complaining about stock thefts and petty crimes committed by the Hottentots and Bushmen: short and one-sided armed clashes then took place during which the Bushmen, who were never united, moved in large numbers north to what later became known as South West Africa, where their remnants have remained till modern times.

Slaves

During the second half of the 17th Century, Malay slaves were imported from Dutch colonies in Asia to work in Cape Town, while during the same period a number of Black slaves were brought in from other parts of Africa (the nearest Black tribes at this stage were still some 1,000 kilometers from the Cape, slowly wandering southwards). They entered South Africa from the North almost at the same time as the Dutch landed in the Cape.

Mixed Marriages Prohibited

In 1682, the Dutch East India Company formally issued written instructions from the Netherlands to the governor of the Cape colony at the time, one Simon van der Stel, to officially forbid all racial intermarriage following a number of marriages between early White settlers and freed slaves.

In 1685, the first law prohibiting interracial marriages in the Cape was formally proclaimed, and a Whites only school had been established for the children of colonists. Eventually the remnants of the Hottentot population, the Malays and Black slaves and a number of Whites, mixed together to produce a mixed race group which later was to be called Cape Coloureds. Some of these mixed racial types did however “pass over” into the officially classified White group, and modern estimates are that about 6 percent of Afrikaners who claim to be White, are actually of mixed ancestry.

Boers (Farmers)

As the number of White settlers grew, so did the first inklings of a sense of national identity – exactly as had happened in all the other major White settlements in the new lands. Dutch was still the dominant language, and the Dutch word for farmer is boer. After many years the Whites who moved into the interior of the country who spoke a form of Old Dutch, began to be called Boers, and by this name they won world renown.

First Encounter with Black People

The farming community began to push evermore eastward from Cape Town, crossing what is the Southern Cape and finally encountering the first major Black tribe, the Xhosa, in the present day Eastern Cape – some 1,000 kilometres from Cape Town – around 1770, some 120 years after the first White settlement was started.

The farmers who moved were called “Trek Boers” (trek meaning move) and they pushed further and further into the interior of the country, motivated partly by a desire to obtain new land but also by an increasing dissatisfaction with Dutch colonial rule at Cape Town.

After meeting the Xhosa in the Eastern Cape, both the eastward migration of the White Trek Boers and the southwards migrating Blacks came to a halt: on the Fish River border between the two racial groups, a series of nine racial wars took place over a space of nearly 70 years (starting in 1781 and only grinding to a halt in 1857), becoming known as the “Kafir Wars”. (Although the term “kafir” has of course come to be derogatory, the actual word itself is of Arabic origin, “khufr”, meaning non NonChristian or Muslim, and thus equally applicable to Whites or any other racial group).

Race Wars and the Self Destruction of Xhosa Power

These race wars severely tested the resolve of the Trek Boers, and later the British settlers in the area, with many atrocities being committed by both sides, mostly in retaliation for earlier attacks, and often sparked off by cattle thefts.

Eventually the wars came to an end in 1857, after a Xhosa prophetess convinced virtually her entire tribe that a spirit had spoken to her and had instructed all the Xhosa to kill their cattle and destroy all their supplies.

On a certain day – 18 February 1857 – the sun would arise blood red in colour and all the dead Xhosa warriors would rise from the dead and sweep all the Whites into the sea – a violently anti-White outpouring which was not unusual for the time.

In what turned out to be a major disaster for the Xhosa, they followed this prophetess’ advice, destroyed their stores, killed virtually all their livestock and settled down to wait for their dead warriors to arise. Fortunately for the Whites, this was where the plan went wrong: on the appointed day nothing happened, and after several weeks, Xhosa power was broken by a combination of starvation and disillusionment.

The British in the Cape

The start of the conflict between Britain and France at the end of the 18th Century saw Britain taking the strategically important step of militarily occupying the Cape: for fear that the Dutch would turn it over to the French and thereby cut the British sea route to the East.

The British occupied the Cape in 1795 to forestall any French interest in the strategic sea route to India and elsewhere.

The British occupied the Cape twice: once in 1795 (they withdrew a short while after) and the second time in 1806 (they stayed on that time). At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, Britain formally purchased the Cape from the Dutch for six million pounds and another colony was added to the growing British Empire. In 1806, the Cape Colony had a White population of some 26,000 – and a slave population of some 30,000, with an estimated Cape Colored population of 20,000.

Mass British Settlement

The British takeover of the Cape saw several changes: the most important of which was the arrival in 1820 of over 3,000 British settlers in the Eastern Cape, recruited especially with British government financial aid to bolster the White population on the eastern border with the Xhosa, where the intermittent race wars were continually threatening to overwhelm the isolated White towns.

This influx of such a large number of English speakers – a near enough 12 percent increase in the total White population within a matter of weeks – soon caused a general Anglicization in the Cape which antagonized the still Dutch speaking Trek Boer population, although many who had stayed close to Cape Town did not object as vocally as those out on the frontiers.

The Anglicization process also extended to the introduction of English laws: in 1822, English became the sole official language; in the same year, the Cape Coloured population were included in the first labour laws and finally slavery itself was abolished in 1833. The British government offered compensation for the 35,000 slaves in the Cape Colony, as it was called then, to the Trek Boers – but this was only paid out in London, making it practically impossible for the majority of slave owners to collect their compensation.

The Great Trek

A combination of factors: the Anglicization policy, the introduction of English law and the then seemingly unending wars with the Xhosas created the dynamo which became known as the Great Trek.

From 1836 onwards, some 15,000 Trek Boer families packed up their goods into canvass covered wagons and set off for the interior, away from British rule. This Great Trek was the final catalyst for the formation of the people who became known as the Boers (the word Afrikaners was only developed late in the 19th century once the language spoken by the White non-English speakers had crystallized).

By the time the Great Trek was over, the Boers had been formed into a distinct national identity of their own, fiercely independent and strongly Calvinistic in religion.

The dangers and epic of the great Trek alone have filled many a book: the effort of having to cross the highest mountain range in Southern Africa, called the Drakensberg (the Dragon Mountains – a deserved name) in ox wagons; the necessity of having to create much of their raw material and many supplies along the way; and the trials and tribulations of doing all of this with entire families in tow, was a truly remarkable achievement, and the trek itself came to assume almost superhuman status and symbolism in the White Boer psyche.

A small group of Trekkers (pioneers) moved into the interior, into what became the Orange Free State and Transvaal, while a larger group crossed the Drakensberg mountains and decided to settle in what was to become Natal.

First Expeditions a Failure

Leaving their jumping off points in the central and eastern Cape, small groups of Whites set off for the interior, with only covered wagons, horses and their ingenuity to guide them as they trekked into the wild, untamed, unknown and dangerous interior.

The first small expedition, started in 1835, ended in complete failure. Jan van Rensburg’s small party was ambushed and exterminated by Blacks on the Highveld (field). Yet another party, led by Louis Trichardt, barely survived attacks by Blacks and was then decimated by malaria, with a few desperately ill survivors finally struggling through to the Portuguese base at Lorenzo Marques (today Maputo).

The first two expeditions were therefore disastrous, producing a fatality rate of well over 80 per cent. Nonetheless, the issues forcing the Boers on did not diminish, and slowly over the next two years support for a new migration grew.

Piet Retief

In 1837, the Port Elizabeth based Boer, Piet Retief, organized an expedition from Grahamstown, after issuing a manifesto outlining his reasons for undertaking

Pieter Mauritz Retief

12 November 1780

Soetendal, Wagenmakersvallei,

Died 6 February 1838 (aged 57)

Hlomo amabuto, uMgungundlovu

the Trek into the interior. After joining with an expedition led by Andries Potgieter for the initial trek north, Retief and his party turned eastwards over the Drakensberg mountains (the Dragon Mountains) in a virtually superhuman effort of unparalleled endeavor and hardship. Little wonder then, that when they reached the apex of the Drakensberg, and the green lands of Natal stretched out before their eyes, they called the land Blydevooruitzicht, or Happy Prospects.

Dingaan

There was however one serious issue: the fierce and warlike Zulu tribe under the leadership of their ferocious chief, Dingaan already occupied the new land. While the bulk of Retief’s party – which consisted mainly of women, children and aged men – encamped along the Blaukraans River, Retief led a party of 70 men and teenage boys on a peace mission to Dingaan at the latter’s chief settlement, or kraal, called Umgungundlovu. The purpose of the mission was to try and peacefully negotiate land for the Trek party from the Zulus.

Dingaan however accused the Trekkers of stealing cattle from him; only after several weeks searching did Retief’s party manage to locate the missing cattle (they had been stolen by a local chief called Siyonkella).

On 2 February 1837, the Boers returned to Umgungundlovu with the missing cattle: on 5 February, Dingaan and Retief signed a treaty (Dingaan signed it with a “X”, as he was illiterate) giving the Boers land in Natal. After the signing of the agreement, the Zulus put on a dancing show and celebration.

In turn the White Boers gave a shooting and horse riding demonstration to the Blacks: confirming the reports Dingaan had already received about these White men who had sticks which could kill at a distance and who had magic beasts which could carry a rider at great speed.

“KILL The White Wizards”

On the following day, 6 February, the 70 White men were up before daybreak. As they prepared to leave to return to their camp where their women and children were waiting, a Zulu messenger arrived. He carried with him a message from Dingaan asking that Retief and his men meet one more time

inside the Zulu king’s enclosure where the two parties would toast their successful negotiations and future friendship. The Whites agreed.

espite warnings, Retief left the Tugela region on 28 January 1838, in the belief that he could negotiate with Dingaan for permanent boundaries for the Natal settlement. The deed was signed by Dingaan on 6 February 1838 with the two sides recording three witnesses each.

Retief and his men made their way to the Zulu king’s inner enclosure. Before they entered the final ring of mud huts and reed walls, they were asked to leave their firearms stacked in a pile outside as a mark of respect to the king: foolishly they agreed, not suspecting that it was all an elaborate trap and that the Zulus had no intention of honouring their word. The treaty between Retief and Dingaan was still in the pouch the former was carrying.

As the White men entered the inner enclosure, the gate was closed behind them. Dingaan greeted the White men, and bid them sit before him. They then drank the crude sorghum beer offered to them, still unsuspecting and full of trust. In the inner enclosure were nearly two thousand Zulus in full combat gear: shields, spears and wooden clubs. Now they had the White men unarmed and outnumbered.

At Dingaan’s command they began dancing, shouting and waving their Stone Age weapons in the air. The White men watched and listened. The Blacks then slowly started moving back and forth: each time advancing three steps and retreating two: gradually they crept closer and closer. At the point where they nearly touched the seated White men, Dingaan jumped up and shouted out “Kill the White Wizards!”

The Murder

Too late the Whites realized the treachery which had been played out upon them: a few jumped up and tried to defend themselves with their small hunting knives, but they were no match for the two thousand heavily armed Zulus. Some of them were strangled to death on the spot by crude ropes made of cut up animal skins: the rest were seized, and along with the bodies of their dead comrades, were dragged outside the royal camp to a hill next to Umgungundlovu, called Hlomo Amabuta, the Hill of Execution.

Retief, his son, men, and servants – about 100 people in total – were taken to kwaMatiwane Hill, a site where Dingaan had thousands of other enemies executed. The Zulus killed the entire party by clubbing them and killed Retief last, so as to witness the deaths of his friends and son. Retief’s heart and liver were removed, wrapped in a cloth, and taken to Dingaan.Their bodies were impaled and left on the hills to be eaten by the wild life.

There the Blacks cruelly executed the remaining Whites, one by one, by clubbing and spearing them to death. Last to be killed was Retief himself, after having been forced to watch his own teenage son be clubbed to death. Once dead, Retief’s heart and liver were cut out of his body and ceremoniously presented to Dingaan as proof that the chief White wizard was dead. The White Christian missionary, Francis Owen, whose mission station was situated on a hill overlooking Hlomo Amabuta, witnessed all these events. Despite the tragedy being played out before his eyes, the Christian Owen made no effort to warn Retief’s party, encamped as they were only a few hours’ ride away. Instead Owen fled to the British trading settlement at Port Natal (Durban) a few days later.

been forced to watch his own teenage son be clubbed to death. Once dead, Retief’s heart and liver were cut out of his body and ceremoniously presented to Dingaan as proof that the chief White wizard was dead. The White Christian missionary, Francis Owen, whose mission station was situated on a hill overlooking Hlomo Amabuta, witnessed all these events. Despite the tragedy being played out before his eyes, the Christian Owen made no effort to warn Retief’s party, encamped as they were only a few hours’ ride away. Instead Owen fled to the British trading settlement at Port Natal (Durban) a few days later.

Whites Massacred

So it was that no news reached the Voortrekker camp of women, children and old men along the Blaukraans river for ten days: the last word they had received was that Retief had been successful in negotiating land from the Zulus and that everything was in order. An atmosphere of joviality prevailed in the camp: the Trek had paid off.

However, the reality was different: during the night of 16 February 1838, the Zulus struck. The Boers’ camps were small, scattered and poorly defended. Filled with a false sense of security, they were easy targets for the 10,000 strong Zulu army sent to annihilate them. Attacking at 1:00 am in the morning, the Zulus fell upon the largely sleeping White camps.

The small camp of the Liebenberg family was quickly overrun and all of its inhabitants murdered as they slept. Next the Zulus made their way to the Bezuidenhout camp: Daniel Peter Bezuidenhout saw his wife, mother and sisters slaughtered by the Zulu spears and although badly wounded himself, he managed to escape and riding his horse, warn some of the neighbouring settlements.

Still the Blacks pressed home the attack: entire families were killed, with one man grabbing his baby daughter and running for miles through the bush clutching his child to his chest, only to find that she was already dead, killed so efficiently by a spear that she had not even cried out. Finally some of the larger camps managed to draw their wagons into a defensive circle, or laager, and the Zulus were warded off.

But the cost had been frightful: nearly 300 Whites had been killed, including 41 men, 56 women and 185 children. Added to the 70 men killed with Retief, the Blacks had killed more than half of all the Whites in the entire Great Trek in Natal.

Weenen

The scenes greeting the survivors as daylight broke on the 16 February were horrendous: where the Zulus had overwhelmed the White camps, entire wagons were drenched with gore. Johanna van der Merwe was found dead with 21 spear wounds; Catherina Prinsloo with 17. Elizabeth Smit lay dead, her breast hacked off, with her three-day-old baby beside her.

Anna Elizabeth Steenkamp described in her diary a wagon filled with 50 corpses, most of them children, drowned in their own blood. The site was thereafter called Weenen, or weeping, a name it has retained to this day.

For a while the entire Great Trek faltered: the Boers grimly held onto their camps, too weak to move on and too weak to stay. The Zulus then turned their attention towards the British trading settlement of Port Natal, besieging the Whites there in what had become an obvious racial war of anti-White extermination. The British garrison, although heavily outnumbered, held onto what would later become Durban, with equally fierce determination, and the Zulus did not manage to break the defences, despite great efforts in this regard.

The Boer Women

After this massacre, the whole Great Trek teetered on the brink of disaster: many wanted to give up and return to the comparative safety of the British ruled Cape, while others then turned their attentions further north even deeper into the interior, into what became the Transvaal and Orange Free State. There, the first piece of land occupied by Whites there was obtained by treaty from the Bataung tribe, and the town of Winburg was established in this region.

The remaining men in the Boer camps in Natal then came to the conclusion that the trek should be abandoned: the trepidations they had suffered in Natal had been far worse than anything they had endured during their stay in the Cape Province, the k****r Wars included. At this crucial junction, the brave Boer women stepped forward and insisted of the men that the Trek continue: too many sacrifices had been made for them to give up now. By cajoling, mocking and in many instances physically taking the lead, the women won the day: the men gave up their plans to return to the Cape and once again drew new strength to carry on.

Piet Uys

However, further setbacks waited: a new commando under Piet Uys tried to avenge the massacre of the White women and children: they were defeated by the Zulus at the Battle of Italeni, which cost the life of Uys and his teenage son. Once again the threat of total defeat loomed along with a loss of White life.

Andries Pretorius

News of the plight of the Trekkers had by now reached the Cape: a wave of support came flooding for the Whites, culminating in the arrival of hundreds of new Trek volunteers. Amongst them was a farmer from Graaff Reinett, Andries Pretorius, a dynamic natural leader who was elected Commandant General by the till then still leaderless Boers in November 1838.

Within a week, Pretorius had organized a Boer commando of 451 men, including three British people – – Scotsmen actually, defenders of Port Natal who wanted to avenge the bloody Zulu attacks on the British settlements. So it was that a combined White Boer and White English speaking commando, armed with two cannons, set off in search of the Zulus.

After six days of running battles with Zulu patrols, Pretorius chose his camp: covered on the one side by the Ncome River and on the other by a deep ditch, or donga, the Boers arranged their 64 wagons in an almost triangular shape, with the longest part of the triangle running across the side of the laager which had no natural defense.

Ever the improvisers, the White party then cut down masses of thorn bushes and placed them in the donga and underneath and between the wagons themselves, a highly effective early barbed wire.

They also hung lanterns on the end of their long oxen whips, which then protruded out over the outside perimeter of the wagons, providing illumination to prevent a surprise night time attack by the Zulus. Later the Blacks would tell that they had been petrified of the magic of the White wizards, in particular the “ghosts” which hanged above the wagons during the night.

The Vow

Then the Boers prayed to their Christian God that if they were granted victory, they and their descendants would celebrate the day for ever more as a sacred day and celebrate it as if it “were a Sabbath”. This vow gave rise the day being called in later times the “Day of the Vow”, although in fact the actual battle, which was celebrated on 16 December, was not the same day upon which the Vow was taken but rather on the day of the battle.

The Battle of Blood River

At dawn on 16 December 1838, the Zulus finally attacked. Each Zulu regiment was led by its commander, the younger men in the vanguard, the older veterans making up the rear. As they moved forward, estimates of their numbers varied from between 10,000 and 30,000. They chanted and stamped their feet in unison; a frightening sight by any account.

The 451 Whites had little illusion of what their fate would be if the tens of thousands of Blacks overwhelmed their tiny position. Pretorius ordered his men not to fire until they were absolutely sure of making a kill: exercising iron self control, the Whites waited until the Zulu battle line had advanced to within ten paces of the wagons: then the White guns opened up on the Black masses, and the Zulu attackers were cut down by their hundreds.

The few primitive spears thrown by the Zulus hardly even reached the wagons. The Zulus fell back, struck down by the White Wizards’ magic killing sticks to which they had no answer. On the river side of the laager, the Zulus at first tried to attack through the water: bringing one of the cannons to bear, the Whites blasted the Black ranks at virtual point blank range, each shot killing dozens of Zulus.

Finally the Whites had fired so many rounds they ran out of cannon shot: once again, they had considered this possibility, and had pre-selected and stored suitably shaped stones, which they now loaded into the cannons, continuing to rain a merciless fire upon the Blacks.

These cannon were unquestionably decisive: the Blacks had never seen such weapons before, and it must have seemed as if the White Wizards now had fire spitting dragons on their side as well. Again and again the Zulus tried to attack: each time they were driven off by the combined White artillery and musket fire.

At no stage did the Blacks even get close enough to stab any White: only two Whites (one was Pretorius himself) were nicked by spears thrown by the Zulus, but that was all. By now, several thousand Blacks had been killed by the White Wizardry.

The Attack

As the Black line wavered once more; Pretorius gave the order to attack. Leading a detachment of 150 mounted men, one wagon was pulled aside and the commando galloped out to ride straight into the foremost Zulu regiment of over 2,000. Dumb struck with terror at the guns, the cannon and now the White Wizards on their huge hoofed beasts, the Zulu line broke in fright and turned tail and fled.

The Blacks tried to outrun the horses: dozens could not and were trampled underfoot. Hundreds tried to dodge the horses and guns by jumping into the Ncome River, which took them above their heads. This was to no avail. The accurate musket fire and the cannons blasted them as they struggled in the river, and the water quite literally turned red with their blood: hence the river became known to this day as Blood River.

The Black attack was broken: the Whites pursued the fleeing Blacks until dark, exacting a violent and bloody revenge for the massacre of the White women and children at Blaukraans. Zulu dead at the battlefield itself totalled over 3,000 – but this does not include those killed off site or who died of wounds elsewhere.

Above: The Battle of Blood River, 1838. The highly Calvinistic Trekkers took their victory as a sign from the Christian God that they were meant to win and the belief in a divine mission in Africa was born into Boer consciousness, with the battle later assuming virtual mythical proportions, being celebrated every year thereafter with church services of thanks.

First Boer Republic

The defeat of the Zulu army at Blood River spelt the end of the Zulu threat to the White settlement of Natal for the moment, and an independent Boer Republic of Natalia was formally established. However, the British interest in the area had increased with the defeat of the Zulus, and a pattern was set which was to dog White history in Southern Africa for the next 60 years: as soon as the Boers achieved independence, the British moved in and annexed the new territory.

By 1843 increasing British encroachment from the Eastern Cape led to a localized war between Boer forces and the British, with a British outpost in southern Natal, Congella, being besieged by Boers. The British managed to lift the siege and disperse the Boers: by 1845 the British had formally annexed the Republic of Natalia.

The Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic

A few Boers remained in Natal: most left, engaging in a second Great Trek over the Drakensberg mountains into the fledgling settlements in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. There two new independent Boer Republics were created, known officially as the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, the latter also being known colloquially as the Transvaal Republic.

Although the British governor of the Cape Colony tried briefly to annex the Orange Free State in 1848, this attempt was rejected by the British government at the time and the independence of the two Boer republics was recognized by Britain at two conventions in 1852 and 1854.

The White settlement of the Transvaal and Orange Free State had not been without incident: although large parts of the territory had been cleared of their original Black inhabitants by an inter-Black war known as the Difequane, there were still a substantial number of Blacks living in the far north and the west: by penetrating up the central parts of the Transvaal the Boers effectively divided the Black tribes into three regions: the Zulus in the east, the Tswanas in the West and the Matabele in the north.

The Battle of Vegkop

It was the Matabele who moved first: attacking a trekker outpost without warning in 1836 at a place called Vegkop (“fighting hill”), they nearly overran the small laager, but superior White technology saved the day and guns overpowered spears. The Boers also had the advantage of horses, which they used to pursue the defeated Matabele (in one engagement, a local Black tribe tried to use cattle as steeds, but this ended disastrously when the cattle broke rank and panicked at the sound of the first Boer gunshots: more Blacks were killed in this engagement by being trampled to death by their “cavalry” than by Boer marksmanship).

The Matabele were then pursued across the Limpopo River, settling in the territory now known as Zimbabwe, where they are to the present day.

Above: Boers fight off the Black Matabele, Vegkop, 1836. Note the Black servant, far left. From the earliest times, Whites in Southern Africa made wide use of Black labour – and this eventually led to their downfall.

After 1854, the Whites in the Orange Free State fought a number of racial wars with a Black tribe called the Basotho – fighting which eventually led to the British formally annexing the Basotho territory to protect the area from further incursions by the Boers. This land became the protectorate of Basutoland in 1868 and in the 20th century was given independence and became the state of Lesotho.

Racial Attitudes

While always having had non-White servants – even taking them with on the Great Trek – the Boers never believed in racial equality, just like the Whites in America, Europe and everywhere else at the time – and adopted a paternalistic and caring approach to almost all non-Whites with whom they came into contact.

This attitude was translated into official state policy in the Transvaal and Orange Free State Republics, where an advanced system of voting for leaders and an early parliament were the norm – but voting was restricted to Whites only.

Indians in South Africa

The British occupation of the Natal saw the creation of large sugarcane plantations in the ideally suited subtropical regions. At first trying to employ local Black labour to harvest the crops, but unrest and theft caused the British to import thousands of Indian labourers directly from India to do the work. The huge influx of Indians into Natal created the Indian population of South Africa, which to this day is still centred in the former province of Natal.

The Republic of the Orange Free State viewed the influx of Indians into Natal with alarm and brought in a law forbidding any Indian settlement inside its borders. This law remained in force in the Orange Free State until the middle 1980’s.

The First Anglo-Boer War 1881-1882

The Boer Republics were primarily agriculturally based, and also, compared to the British ruled Cape, comparatively poor. The discovery of diamonds in the interior – in a region claimed by both the British and Boers, called Griqualand West, caused a fresh wave of White immigration from Europe, mainly British but also small numbers from other European nations, including a group of European Jews who were soon to wield great influence in the affairs of the region.

The influx of British settlers caused the already strained relations between the Boer Republics and the British to deteriorate. The Boers were not only politically weak but also militarily divided, with the result that the British were able to annex the Transvaal Republic in 1877 with a tiny force which met no resistance at all.

Within a few days, the British flag was hoisted in the Transvaal capital, Pretoria, (named after the Boer leader at the battle of Blood River) and British rule was extended into the interior without a shot being fired.

It took three years and a Herculean effort on the part of three young Boer leaders to organize their people and to motivate them into fighting the British occupation of the Transvaal: eventually in 1881, a Boer rebellion finally broke out. The British were unexpectedly badly beaten by a Boer army at the battle of Majuba in February 1881, and the British then announced that they were prepared to restore self-government to the Transvaal. One of the young Boer leaders of the rebellion, Paul Kruger, was elected president of the once again independent Boer republic in 1883.

The British Race War with the Zulus

The British had in the interim found themselves plunged into the race war which the Zulus had started against the White Boers. In 1872, the White population of Natal was put at 17,500 – while the Zulu population was estimated at some 300,000; with the Indian labourers, who had come to the country voluntarily and who were paid for their labour, numbering some 5,800.

Above: Lieutenants Coghil and Melville die trying to save the Colourss of the British 24th Regiment after the Zulu victory at Isandhlwana. The Colours were never found.

In the eyes of the Zulus however, the White British were no better than the White Boers: both were invaders. The presence of the Indians was also resented by the Zulus, creating a tension between these racial groups which was to sputter on for over a century, with a great Zulu-on-Indian massacre occurring in 1948.

In 1878, the Zulu king, Cetshwayo, assembled an army estimated at 60,000, with obvious intent of attacking the Whites in Natal. The British were aware of his intentions, and on 12 January 1879, White British troops formally invaded Zululand with the intention of forcing the Black army to disband.

On 22 January, around 20,000 Zulu warriors crept up on British soldiers camped at an isolated place called Isandhlwana. By the afternoon, after a fierce battle, the Whites had been all but wiped out – 1500 White soldiers had been killed, with only six surviving out of the entire regiment. Later on the same day, a force of about 4,000 Zulus attacked the small British outpost of about 140 soldiers at Rorke’s Drift, expecting a swift victory. Hours of bitter hand-to-hand fighting followed, and the Blacks were eventually defeated, being forced to retreat with heavy losses. It was not until 29 March at the Battle of Khambula, that the tide finally turned in favour of the British, and in July 1879 that the Zulus were beaten at the Battle of Ulundi, a defeat which finally broke their power.

The British found, to their anger, that the Zulus had acquired White firearms, despite official measures and laws making it illegal to provide Blacks with firearms – it later turned out that individual Boers had supplied the Zulus with weapons in the (correct) hope that they would use them against the British.

Second Boer Republic in Natal

In the far north of Natal, in land previously agreed as belonging to the Zulus, a small Boer population established themselves after providing military assistance to one of the Zulu factions which came to dominance in Zulu politics: this republic of Northern Natal was eventually to join up with the larger Boer Republic of the Transvaal, giving the latter access to the coast for the first time.

The Second Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

The discovery of gold in the southern Transvaal in 1886, caused a new wave of British and European Jewish immigrants to come flooding into the Transvaal. The number of immigrants swelled: in certain areas like Johannesburg, the city founded at the centre of the gold bearing reef, British and other non-Boer elements greatly outnumbered the Boer population.

The Boer Republic refused to grant the new immigrants voting rights, correctly foreseeing the loss of political power, and this “Uitlander” (‘Foreigner”) question was to serve as the spark for the Second Anglo-Boer war of 1889 – 1902, the one that is most often remembered in the annals of history.

After protracted negotiations between the British government at the Cape, headed by one Cecil John Rhodes, and the Boer president, Paul Kruger broke down, a small Uitlander rebellion broke out in Johannesburg. Simultaneously a small private English militia under the leadership of one of Rhode’s adjutants, actually invaded the Transvaal Republic. The invasion and rebellion were quickly suppressed by the Boer forces, but the die had been cast; war between the Boer Republics and the British was thereafter inevitable.

Boers Strike First

Sensing that war was near, the British began moving troops up to the borders of the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republics, and started preparations to ship out further troops from Britain. The Transvaal President, Kruger, sent an ultimatum to the British administration in the Cape to stop the troop build up or the Boers would regard it as an act of war (which it of course was).

The British ignored the ultimatum, and in October 1899, the Boers went over to the offensive, launching two pronged invasions in British ruled Natal and the Northern Cape. The White population figures of the Boer Republics at this stage of the proceedings make interesting reading: in total the White population of the Transvaal and Orange Free States State was just over 200,000, and together with 2,000 Boer sympathizers recruited from Natal and the Cape, the Boer armed forces in total were never more than 52,000 at any one stage in the three year war which followed.

The British in the other hand had 176,000 soldiers alone in the Cape by the end of 1899, and by the end of the war itself had deployed 478,725 soldiers in the field: nearly twice as many military personnel as the entire Boer population, men, women and children included.

Initial British Defeats

At first the war went well for the Boers: several British defeats followed one another in quick succession, created by the skilful use of trenches by the Boers and unconventional mobile tactics. Another advantage, exploited to the hilt by the Boers, was their modern semi-automatic Mauser rifles – a gift from the German Kaiser – while the British still had manual loading Lee-Enfield rifles as their main infantry armament.

The Boers laid siege to three towns inside British held territory: Mafikeng and Kimberley in the Northern Cape and Ladysmith in Natal. It was however in besieging these three towns that the Boers lost their chance of winning the war. Initially the plan had been to strike down into Natal and seize the port of Durban, whilst simultaneously seizing the large ports in the Cape (Port Elizabeth and eventually Cape Town itself) thereby preventing the British from sending in more troops.

However, the main Boer force became bogged down besieging what were in reality relatively unimportant military targets, and the British were able to land many thousands of troops in the country unmolested.

Inevitable British Victories due to overwhelming numbers

Eventually the sieges of all three towns were lifted and the British then pressed home their military superiority, occupying Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, and Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal, in quick succession.

The British then expected the Boers to surrender after the fall of their major cities: but instead the remaining Boer forces – now numbering only some 26,000 – started a hit and run guerrilla war which was to last from 1900 to 1902. Operating in the open veld (field), the Boer guerrillas could rely on provisions and support from the rural Boer community, and as a result the British occupation only extended as far as the range of their guns: as soon as they moved out an area it was quickly re-occupied by Boers, who then waged a highly effective campaign of sabotage and raids against British columns.

Scorched Earth and Concentration Camps

By mid 1900, the Second Anglo-Boer War had been raging for well over a year: the overwhelming British force had occupied all the major towns and centers of the Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, and the Boers had been forced to resort to hit and run guerrilla tactics in the open veld (field).

The Boers continued to inflict defeats upon the British in this way: so much so that eventually the war was to cost the British government £191 000 000 (191 million Pounds – a fortune by 1901 standards, and many hundred times that amount today).

By mid 1900, however, the British had become exasperated with the military situation: the Boers seemed to be able operate with impunity in the veld (field): a new course of action was decided upon. In the last months of 1900, the British began to build what eventually became 45 separate concentration camps, established to systematically remove women and children from their farms to prevent them aiding and supplying the Boer soldiers (“burgers”) in the field.

The British ironically justified rounding up thousands of women and children – something unprecedented before in any other war which the British Empire had fought – in a memorandum issued by the British commander, General Kitchener, on 21 December 1900. In the memorandum issued at his headquarters in Pretoria, Kitchener explained the rounding up of the women was to protect them from the Blacks (!), stating that “seeing the unprotected state of women now living in the districts, this course is desirable to assure their not being insulted or molested by natives.” (Circular Memorandum No. 29, from the archives of the Military Governor, Pretoria; as quoted in “To the Bitter End: A Photographic History of the Boer War 1899 – 1902,” Emanoel Lee, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1985; page 163).

Kitchener was very clear that this was a war against the White Boers, and not the Blacks. The exact language he used in the 21 December 1900 memorandum may seem antiquated, but it reflects not only the style of the time but also the deliberate policy of causing as much damage as possible to the Whites and as little damage as possible to the Blacks: “With regard to the natives, it is not intended to clear ****** locations but only such ******* and their stock as are on Boer farms. Every endeavour should be made to cause as little loss as possible to the natives removed and to give them protection when brought in. They will be available for any works undertaken, for which they will receive pay at native rates.” (Circular Memorandum No. 29, from the archives of the Military Governor, Pretoria; as quoted in “To the Bitter End: A Photographic History of the Boer War 1899 – 1902,” Emanoel Lee, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1985; page 163).

So it was that the British started not only rounding up as many Boer women and children as they could, but also destroying the farms, their only source of survival. The evacuation of the farms was accompanied by the burning and dynamiting of all farm houses and buildings. Poultry, sheep and cattle were slaughtered, the houses looted and all fruit trees, grain or other crops burned down. This is not to say that all the British undertook this task with relish: many ordinary British soldiers were themselves appalled at what they were ordered to do. This revealing insight into how the farms were cleared comes from a soldier who took part in such an operation:

“. . . Only the women are left. Of these, there are often three or four generations: grandmother, mother and family of girls. The boys over thirteen or fourteen are usually fighting with their papas. The people are disconcertingly like the English, especially the girls and the children – fair and big and healthy looking. These folk we invite out into the veld (field)t or into the little garden in the front, where they huddle together in their cotton frocks and big sunbonnets, while our men set fire to the house . . . Sometimes they entreat that it may be spared, and once or twice in an agony of rage they have invoked curses on our heads. But this is quite the exception, as a rule they make no sign, and simply look on and say nothing. One young women at the farm yesterday . . . went into a fit of hysterics when she saw the flames breaking out, and finally fainted away.’

“I wish I had my camera. Unfortunately it got damaged and I have not been able to take any photographs. These farms would make a good subject. They are dry and burn well. The fire bursts out of windows and doors with a loud roaring, and black volumes of smoke roll overhead. The women, in a little group, cling together, comforting each other or holding their faces in each others’ laps. . . . while on the top of the nearest high ground, a party of men, rifles in hand, guard against a surprise from the enemy, a few of whom can generally be seen in the distance watching the destruction of their homes.” (LW Phillips, “With Rimmington”, Edward Arnold, London, 1902).

From the victims’ point of view, the removals were bewildering and terrifying. This extract from the diary of Alie Badenhorst, translated by Emily Hobhouse, reveals the panic and fear which accompanied these removals:

“I packed, and took bedding and tried to pack that also, but I was so crushed I did not know what I was doing, and they (the British) kept saying ‘quick, quick’ so I gathered a few necessities together and thus was I driven forth from my home. It was the 15th April 1901 never to be forgotten. My children cried; the two youngest boys were pale as death and held me fast; the little one kept crying for his chickens. I had to give him courage; and so we were carried, all of us, away.” (Alida Badenhorst, translated E, Hobhouse, “Tant Alie of Transvaal: Her Diary 1880-1902”, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

Filson Young of the Manchester Guardian wrote an account of the actions as follows:

“…The burning of the houses that has gone on this afternoon has been a most unpleasant business . . . in the course of about ten miles we have burned no fewer than six farmhouses. . . . in one melancholy case the wife of an insurgent, who was lying sick in a friend’s farm, watched from her sick husband’s bedside during the burning of her home 100 yards away. I cannot think what punishment need take this wild form; it seems as though a kind of domestic murder were being committed while one watches the roof and furniture of a house blazing . . . I stood till late last night before the red blaze and saw the flames lick around each piece of furniture – the chairs and tables, the baby’s cradle, the chest of drawers containing a world of treasure; and when I saw the poor housewife’s face pressed against the window of the neighbouring house, my own heart burned with a sense of outrage.” (F Young, “The Relief of Mafeking”, Methuen, London, 1900).

Transported in open wagons, and sometimes in open flatbed trains, the Boer women and children so evacuated were taken to the camps which were scattered all over the country, from Howick in Natal through to Kroonstad in the Orange Free State. The terrain upon which the camps had been built was poorly chosen: exposed to the elements and under supplied. Too many people were assembled in too short a time without adequate preparation. The administrative personnel and medical services were inadequate, the rations unsatisfactory; there were dishonest contractors and inefficient officials who were unable to cope with the epidemic of measles and pneumonia which broke out. The wave of evacuees soon overwhelmed the inadequate preparations the British had taken. In December 1900, Milner, the Governor general of the Cape Colony, wrote:

“We were suddenly confronted with a problem . . . which it was beyond our power to properly grapple, and no doubt its vastness was not realized soon enough. The first of the suffering resulted from inadequate accommodation, it was originally meant to house the refugees in wooden shelters, but there was not sufficient material for enough of them to be made.” (SB Spies, “Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics, January 1900 to May 1902”, D.Phil. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1973, as quoted in “To The Bitter End: A Photographic History of Boer War 1899 – 1902”, Emanoel Lee, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1985; page 177).

Internee Alie Badenhorst described the conditions in the camps so:

“…One had to make little fireplaces in front of the tents – tents that must serve as sitting room, pantry, bedroom and dining room in one, and they were of a size that were but one small bed and a table therein, there was no room to turn; and then there were a number of children as well! Most of the poor women had not even brought a bedstead with them because they were seized in such haste.”

“When we came, the women received eatables three times a week. Tuesday, meat; Wednesday, meal, sugar coffee, salt; and on Saturday, again meat. The food stores were not near the camp, quite ten minutes walk, and they had to carry it all. For each person there was 7lbs of meal a week, no green food and no variety; the sugar was that black stuff we would have given our horses on the farm to stop worms . . . the coffee was some mixture, no-one could rightly say what coffee it was, some said acorns, others dried peas – but it was all a very sore trial for us to bear, we, who were so used to good food, vegetables, milk and mealies.” (Alida Badenhorst, translated E. Hobhouse, “Tant Alie of Transvaal: Her Diary 1880-1902”, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

The winter of 1901 was particularly severe: even British troops in the field froze to death. In the camps, the damp and cold conditions played havoc amongst the tents: sickness began to spread amongst the children, and soon reached the adults. The death toll began to mount dramatically: the camp at Brandfort had the highest death rate during the worst months.

Alie Badenhorst wrote: “Worst of all, because of the poor food, and having only one kind of food without vegetables, there came a sort of scurvy amongst our people. They got a sore mouth, and a dreadful smell with it; in some cases the palate fell out and the teeth, and some of the children were full of holes or sores in the mouth. And then they died . . . the mothers could never get them anything . . . there were vegetables to be bought outside, but the head of the camp was strict and did not allow them to go out of the camp . . . For it was this day, the 1st December, that old Tant Hannie died . . . I never thought with my eyes to see such misery . . . tents emptied by death.

“I went one day to the hospital and there lay a child of nine years to wrestle alone with death. I asked where could I find the child’s mother. The answer was that the mother died a week before, and the father is in Ceylon (a prisoner of war) and that very morning her sister of 11 died. I pitied the poor little sufferer as I looked upon her . . . there was not even a tear in my own eyes, for weep I could no more. I stood beside her and watched until a stupefying grief overwhelmed my soul . . . O God, be merciful and wipe us not from the face of the earth.” (Alida Badenhorst, translated E. Hobhouse, “Tant Alie of Transvaal: Her Diary 1880-1902”, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

Above: The Boer Holocaust: Boer children, emaciated through disease, photographed in British concentration camps in South Africa, 1900-1902. Eventually 27,927 women and children were to die in this way.

Up to October 1901, the number of inmates in the 45 camps increased to 118 000 Whites and 43 000 non-Whites. The death rate was 344 per thousand amongst the Whites; at one stage in the Kroonstad camp the death rate was 878 per thousand.

Eventually 27,927 Boers died in the camps, of whom 4177 were adult women and 22,074 were children under the age of 16. Since the entire Boer population in both republics was just over 200,000, the mortality rate meant that just under 15 percent of the entire Boer population was wiped out. Such a figure is of genocidal proportions.

These figures are even more revealing when the actual combat fatalities for the entire war are reviewed: some 7091 British soldiers died, while on the Boer side some 3990 burgers were killed, with a further 1081 dying of disease or accident in the veld (field). Twelve percent of Boer deaths were battle related; six percent died from other causes while on commando; 17 percent were adults in the camps and 65 percent were children under the age of 16 years.

It has been estimated that without this loss, the White population of South Africa would have been as much as a third larger than what it eventually became.

Boer Surrender

Although the guerrilla war itself was reasonably successful – with one Boer commando under the able guerrilla leader general, Jan Smuts, raiding so deep in the Cape that they came within sight of Table Mountain in Cape Town – the pressures brought to bear by the concentration camp issue forced them to eventually surrender or face total extermination. In 1902, the Treaty of Vereniging brought the war to an end, and Britain formally annexed the Transvaal and Orange Free State.

BRITISH ENDORSE BOER POLICY

Although the Boer Republics had denied citizenship or voting rights to the Blacks, they were not alone in this policy: the British strictly enforced similar policies in their parts of Southern Africa, with the only exception being granted to a small number of Cape Coloreds who could meet very stringent property requirement stipulations.

After occupying the Boer republics, the British actively proposed keeping the Blacks voteless. Segregation was accepted as a perfectly normal and desirable state of affairs, and it was not even considered necessary to make laws in this regard, so universally was the practice accepted. It was not a case of the Blacks being disenfranchised: they had never had the vote, so they were un-enfranchised and remained so.

In this way the administration of the four colonies – the Cape, Natal, the Orange Free State and Transvaal – was carried out exclusively by Whites, with in many cases in the former Boer republics even by former Boer civil servants returning to their pre-war posts.

The Union of South Africa

This policy of keeping the Blacks un-enfranchised was carried over into the next important political development in South Africa: the union of the four colonies in 1910. In 1909, talks were started between the administrations of the four colonies over the idea of union, and after protracted negotiations, the Union of South Africa formally came into being in 1910, a dominion under the British monarch.

A clause in the legislation which created the Union stated that the constitutional position of the Blacks – un-enfranchisement – would remain and could be changed only by a two-thirds majority vote of parliament. Thus it became so that the only non-Whites who had any vote were the handful of Coloreds in the Cape: but even they themselves were prohibited from standing for parliament, and could only vote for White candidates (another law introduced by the British when the Cape was still ruled as a separate colony). These limited voting rights were themselves abolished in the 1950s.

The British also actively kept the Indians out of the political pot by denying them voting rights as well. In addition to all of this, by the time of the Union it had also been de facto accepted that certain regions of the country were dominated by Black tribes and that as a general rule these areas were to be left alone, although in most cases these regions had a White governor over them.

Black Homelands

In this way the territories of Lesotho, Swaziland and Botswana came into being (all British owned territories and carved up on a racial basis: the Tswana Blacks in Botswana, the Sotho Blacks in Lesotho and the Swazi Blacks in Swaziland.)

The other territories, earmarked for Black tribes, were, in exactly the same way,split according to where the majority of each tribe lived: the Xhosas in the Eastern Cape, the Zulus in Natal and so on. These other territories (the Eastern Cape, parts of Natal etc.) were later to be formalized as tribally owned Black homelands – and it remains one of South African history’s supreme ironies that the Black tribal homelands created by the British (Lesotho, Swaziland and Botswana) were given perfectly legitimate international status,while the identically created Black tribal homelands given independence by the later White government of South Africa, were rejected as being racist – even by the British government.

This section deals with the creation of Apartheid in South Africa and its ultimate, inevitable end – relying as it did upon Black labour over which a White minority tried to enforce social segregation.

THE 1913 Land Act DIVIDES THE LAND BETWEEN BLACK AND WHITE – (note the so called apartheid government only came into existence in 1948) ???

In 1910, the Union of South Africa was created under British rule, out of the two former Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, together with the already established British colonies of Natal and the Cape.

The new Parliament, created as a result of the Union, was led by Cecil John Rhodes (a British Citizen) and his generals. In 1913, they turned their attention to the issue of the reserved Black areas, and, following the American example with the Amerinds, formally enshrined the right of Blacks in these tribal areas. This was the Land Act of 1913, which also had one rider: they prohibited Blacks from owning any land outside of these now formalized homelands.

The ruling party (the British) also had as its theme reconciliation between Boer and Brit. This attempt to create unity on racial grounds, trying to bridge the cultural/ethnic differences, led to the creation of a new generic term for all Whites living in the Union of South Africa: South Africans. The terminology Boer and Brit was dispensed with. The Dutch language had in the interim started to develop a form of its own, and became known as Afrikaans: and those who spoke it were called Afrikaners, no matter if they were originally Boers or Dutch speakers who lived in the British ruled Cape and Natal before the Anglo-Boer War.

The ANC was Founded in 1912

At a time when South Africa was changing very fast. Diamonds had been discovered in 1867 and GOLD in 1886. Mine bosses wanted large numbers of people to work for them in the mines. British Colonial laws and taxes were crafted to force Native peoples to leave their land and serve these British interests. The most severe law the British Colonialists passed was the 1913 Land Act, which prevented African Blacks from buying, renting or using land, except in the Reserves. Many communities and families immediately lost their land because of the British 1913 Land Act. And, thus, for millions of other black people, it became very difficult, if not impossible to live off the land. The Land Act caused overcrowding, land hunger, poverty and starvation.

National Party Founded in 1914

The attempt to create White unity was however rejected by a significant number of English and Afrikaans speakers. One Boer general, James Hertzog, founded a new party in 1914, the National Party (NP) which was to play a leading role in South African history for the next 80 years. Hertzog demanded that the Afrikaans language – which was still not recognized, with English being the official language of the country, be granted equal status with English, and that the country have its own flag, and not the British flag. These aims were only to be achieved in the middle 1920’s.

World War One and the Boer Rebellion of 1914

The outbreak of the First World War split the Whites even further: fuelled not so much by a pro-German sentiment, but rather by an anti-British sentiment, many Afrikaans speakers refused to support the South African government’s decision to declare war on Germany.

A number of Boer leaders started a rebellion in the year that the war broke out, demanding the restoration of the Boer Republics, obviously hoping to capitalize upon the British being distracted by having to meet the demands of a war in Europe.

The South African government – still in the hands of the pro-reconciliation Afrikaans speakers – suppressed the rebellion, which saw the deaths of a number of its ringleaders. Despite the violence, the NP still polled well in the 1915 election, although not enough to dislodge the pro-reconciliation grouping which had drawn more English speaking support after entering the war on the side of Britain.

The first engagement of the war from the South African side was the occupation of German South West Africa, a territory which would be mandated to South Africa by the League of Nations after the First World War. This territory would later become known as South West Africa, and be the scene of a major race war between White South Africa and Black insurgents. (Still later the territory would become the country of Namibia). The South African army – which was recruited on a volunteer basis – then went on to participate in the occupation of the German East Africa – today Tanzania.

South African troops also fought in large numbers on the Western Front in France, fighting in the Battles of Delville Wood, Paschendale and many other famous and bloody clashes.

The Racist Communists and the White Revolt of 1921

The whole country was therefore split three ways: between English speakers, Afrikaans speakers and Blacks, with neither of the two White groupings wanting to integrate with the Black group. So it was that even the South African Communist Party, started largely by South African Jews based in Cape Town, initially directed itself openly only to White workers.

In 1921, leaders of the country’s gold-mining industry decided to replace White labour with Black and Chinese labourers in an effort to cut costs. This move led to a major uprising in March 1921 called the Rand Revolt, led initially by the Communist Party with the official slogan of “White Workers Unite for a White South Africa” – the sight of this slogan along with the hammer and sickle flag was for long afterwards a great source of embarrassment for the Communist Party, which soon thereafter devoted itself to attacking the White power structure and started enrolling Blacks as members. (A photograph exists of this famous slogan being prominently displayed on a banner during a main Communist march during the Rand revolt.)

Above: Racist Communists organize the 1922 Rand Strike, under “Workers Unite for a White South Africa.” The strike was organized against the capitalist mine owner’s plan to bring in cheap non-White labour to replace more expensive Whites on the gold mines, and erupted into a full scale rebellion. Shortly afterwards, the Communist International instructed the SA Communist party to drop its racist line and become focused on helping the Black cause in South Africa, a task it dutifully fulfilled. Needless to say, the overtly racist approach of the early SA Communist Party is ignored by that party in present times.

The revolt was suppressed at a cost of 200 dead, with the fledgling South African air force (the second oldest such force in the world, being started shortly after the British Royal Air Force) bombing rebel strongholds in Johannesburg.

National Party in Power

Although the revolt was crushed, three years later, during the 1924 election, the National Party came to power for the first time, mainly on election undertakings to protect White workers from non-White labourers taking their jobs. Race had become an important electoral issue for the first time.

Shortly after taking power, the NP government duly introduced the first colour bar legislation, which prevented Blacks from being employed in certain categories of jobs, these being reserved for Whites only.

The Great Depression and World War Two

The NP remained in power alone till 1933, when the effects of the Great Depression forced a coalition government with the pro-reconciliation faction under the former Boer War general Jan Smuts. This coalition ruled till the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

When the Second World War broke out, certain small factions of Afrikaners were decidedly pro-Hitler and had even formed tiny Nazi parties, none of whom received any significant electoral support. A bare majority of the South African Parliament voted in favour of entering the war on Britain’s side: as a result the coalition government broke down and the NP went into opposition, having voted against going to war for Britain.

Outside of Parliament, militant Afrikaners organized themselves into a movement known as the “Flaming Ox Wagon Sentinel” and through this organization engaged in numerous acts of sabotage and violence in an attempt to keep the country’s volunteer army deployed internally, rather than being used against the Germans and for the British.

South African troops fought against the Italians in Abyssinia, and in North Africa as part of the British Eighth Army, taking part in numerous famous battles such as El Alamein. They then went to take part in the invasion of Italy in 1943, fighting at Monte Casino, being part of the occupation troops in Rome and ending the war in northern Italy. The South African Prime Minister, Jan Smuts, was instrumental in founding the United Nations and helped to draft its founding charter.

The Election of 1948

In 1948, an election alliance between the NP and a number of smaller factions succeeded in ousting the Smuts government, despite the former winning a minority of votes (the skewed first past the post Westminster electoral system allowed Smuts to gain the larger number of votes but the fewer seats).

Above: DF Malan, the National Party leader who barely won the 1948 general election in South Africa, on a pledge to the all-White voters to enforce the policy of Apartheid, or strict social segregation.

It is from the election of 1948, that Apartheid, or the policy of racial segregation, is deemed to have become official policy in South Africa. The reality is however that segregation and the recognition and creation of Black tribal homelands had preceded 1948 by centuries.

The very first segregation had in fact occurred soon after the first Dutch settlement at the Cape in 1652: in 1653, the Dutch had planted a particularly large hedge to mark the border between their territory and Hottentot/Bushman territory (parts of this massive hedge can still be seen in Cape Town) and the formal recognition of the Black tribal homelands by the British authorities has already been discussed. In fact, all the National Party did in 1948, was make statutory a de facto situation, and very little else.

At the time this was perfectly in line with developments elsewhere in the world, especially in America where legislation also governed the access of Blacks to certain public places, schools and the like. The first “Whites Only” signs only appeared in South Africa long after they had first appeared in America. The NP set about further imitating many American states by outlawing racially-mixed marriages, instituting a system of racial classification and finally, by legislation, defined residential and business areas for the different races.

Black Resistance

The Communist Party had in the interim renounced its racist past and worked full time against the White government, organizing trade unions and strikes. In 1950, the White government passed the Suppression of Communism Act, which outlawed the Communist Party – an act which was only repealed in 1990. The main Black resistance movement was started in 1912 – the African National Congress, which would later go on to become the government of South Africa at the end of the era of White rule. The ANC would form a firm alliance with the SA Communist Party throughout its years of struggle against the White government, and for many years after its assumption of power as well.

WHITE POLITICIANS MISS THE Real Issue – THEIR DEPENDENCE ON BLACK LABOR

The normalization of racial segregation by the NP did not address the real issue which has faced every White country, culture or authority since the start of White history: namely, the contradiction of allowing huge numbers of non-Whites into the territory in question to do the labour; whilst trying to prevent that civilization from being overwhelmed by foreign numbers. In fact, it cannot be done.

White South Africa was no different in this regard to any of the previous White societies: the Aryans in India in the year 1500 BC, also lived in a country where the majority of the population was non-White: they too introduced all manner of laws trying to prevent racial mixing but all the while used the non-White labour. Eventually the sheer numbers of non-Whites grew to the point where it was no longer feasible to exercise control – simply put, the situation was reached where there were simply not enough Whites to control the entire territory, and the White civilization was overwhelmed by non-White numbers and sank.

In South Africa, almost every White household had one or more Black workers, with farmers very often having dozens to work the huge farmlands, more often than not living on the premises; in the mines, the economic heart of the country, the vast majority of common labourers, numbering many thousands, were Black; all over the country the overwhelming majority of labourers were Black.

Above: Central Johannesburg, mid 1970s: a White policeman checks a Black labourers “pass book” – a document which entitled that Black person to be present in the White urban areas of South Africa provided that Black person had a job. Nothing better illustrated the inherent flaw in Apartheid than this state of affairs.

Over this mass of economic integration, the Whites of South Africa attempted to enforce social segregation and still maintain a White government: it was doomed from the start, as it was in Aryan India, in ancient Persia, in ancient Sumeria, in ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece and ancient Rome.

All that happened in South Africa that was different was that the number imbalance occurred even faster than in the older civilizations, and White control was overwhelmed at a quicker pace.

Black Birth Rate JUMPS WITH WHITE AID

At the same time, Western medicine was made available on a massive scale: the largest hospital in the Southern Hemisphere was erected in the Black township of Soweto, outside Johannesburg, specifically for the Black population. Infant mortality rates for Blacks, while still far higher than for Whites, fell dramatically, and were way below that of the rest of Black-ruled Africa. This rapid population growth, also typical of non-White populations residing in White ruled countries throughout history and elsewhere in the modern world, put additional pressure on the demographic makeup of the country.

White Reaction

The White government was forced to think out ever more stringent and oppressive laws to protect the Whites as the Black population continued to leapfrog in numbers year after year. Soon economics became a secondary issue in everyday politics when compared to the racial issue. Black resistance had also been growing along with the increase in that racial group’s numbers.

At first peaceful, the Black resistance groups turned to violence after it became clear that the White government was unmovable on certain basic issues, and failed to see the inherent contradiction between social segregation and economic integration.

Finally, after a section of White policemen shot down 69 Blacks during a demonstration in Sharpeville to the south of Johannesburg in 1960, open violent political rebellion broke out amongst the Black population. The White government reacted by banning the main Black resistance organizations, the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (the latter being an openly Black racist party which had separated from the ANC in 1959). These two organizations then launched a campaign of armed resistance to White government, which lasted some 30 years, with varying degrees of success. In reality however, despite large numbers of Blacks being co-opted into the state structures (in the form of police and army units) South Africa erupted into a long running low intensity race war, with Black and White physically fighting it out for political control. The Whites had the technological advantage; the Blacks always had the greater numbers.

As the Black resistance was closely allied to the South African Communist Party it soon received large amounts of material aid from the Soviet Union (further fuelling the allegations made by the White government that the Black resistance was a Communist inspired effort – an allegation that was of course untrue and made for propaganda purposes, as the Black resistance groups took aid from anyone who gave it to them, which included many fanatically anti-Communist Arab countries). The dividing issue was race, not ideology.

South African Military

Despite the aid to the Black resistance movements, the South African military was developed into a virtually self reliant extremely powerful force, certainly the strongest conventional force in all of Africa. The battle was however, apart from on the border in South West Africa (see below), never to be waged conventionally.

The Black resistance movements adopted a guerrilla hit and run policy of attacks on strategic targets, in certain aspects ironically mimicking the Boer guerrilla war against the British of the period 1900-1902. To combat this unconventional war, the South African Police were given extended powers of detention and other draconian measures – all of which could only be short term fire fighting measures, as the main issue: that of preventing majority Black occupation of the country – was never addressed by any Apartheid laws.

The Republic of South Africa

In 1961, the South African government declared itself a republic and formally withdrew from the British commonwealth – the aspirations of Afrikaner independence had once again been fulfilled.

Above: A poster issued during the 1961 referendum, makes the issue at stake very plain: either stay in the British led Commonwealth and be forced to accept Black rule, or break away and become a White ruled Republic. A slim majority of voters chose the White Republic option.

The White Republic of South Africa was noted for many things, not the least of them many world first in technological breakthroughs. In this way the very first heart transplant was carried out by an Afrikaner, Chris Barnard, in the segregated hospital of Groote Schuur in Cape Town, in 1962; the first truly properly successful industrial plant which converted coal into oil was set up at Sasolburg in the Orange Free State (the technology had first been developed by the Germans during the Second World War at the Buna rubber plant at Auschwitz); the country became self reliant in the manufacture of arms and sophisticated weaponry (leading to a thriving arms export business) and also developed its own nuclear weapons.

Black Homelands Revisited

At the same time the White government starting giving practical application to the policy of “Grand Apartheid”. Imitating the British, independence was given to a number of traditional Black tribal homelands, the first in the mid 1970’s.

In this way, the White government deluded itself into thinking that Black political aspirations could be satisfied in the exercise of voting for these tribal homelands, despite huge numbers of these tribe members living outside the borders of these states – in the urban areas.

This policy was naturally doomed: it never seriously addressed the issue of the use of Black labour in the White areas, and those Blacks who did agree to take up the reins of government in these Black homelands were (usually accurately) rejected as puppets of the Whites by the majority of Blacks.

The White government also refused to adjust the size of these traditional tribal areas to fit in with the changed demographics, stubbornly insisting that their land area – some 13 percent of the country’s surface area – could accommodate what was rapidly becoming over 80 percent of the total population.